|

We need your help to keep the KWE online. Jim Doppelhammer, our longtime webhost, has passed away and his webserver will go offline

in 2025. The entire KWE website must be migrated to a modern server platform

before then. If you value this resource and want to honor our veterans by keeping their stories online

after 2024, please donate now.

For more information, click here.

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| Back to "Memoirs" Index page | |||||||||||||||

Franklin "Jack" ChapmanSanta Fe, New Mexico -

- Jack Chapman |

|||||||||||||||

Cherokee Warrior Contents:

PrologueThere is certainly no glory or honor to being captured and incarcerated as a Prisoner of War. While there is no disgrace, it’s a traumatic, frustrating and often humiliating experience to be coerced into circumstances and situations beyond one’s control, and more significantly, having to unconditionally surrender one’s most precious right...… Freedom! The Geneva Convention is a treaty agreed upon by several nations, and put into effect in 1950, for the protection and the conduct of the prisoner of war. In general, its main purpose is to provide rules that prisoners of war must be treated humanely. Specifically forbidden are violence to life and person, cruel treatment and torture, and outrages on personal dignity, in particular, humiliating and degrading treatment. As a young soldier, this and the words “If captured” had little or not significance to me……… except when it became my reality and personal nightmare for three years. Sir Winston Churchill, former Prime Minister of England, so aptly described the ordeal of a prisoner of war as follows:

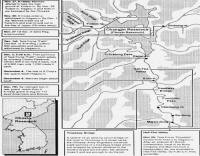

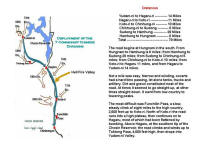

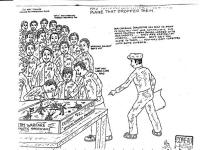

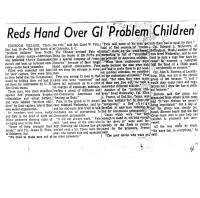

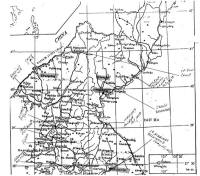

During the Korean War of 1950, I and hundreds of my fellow servicemen were captured by Communist Forces and spent the next three (3) years as Prisoners of War. Although we had little or no training in the Communist tactics of torture and brainwashing, many valiantly resisted and some survived until 1953, when we were finally liberated and put under control of the United Nations at Panmunjom, South Korea. This is my story, an actual, factual and chronological account of events occurring before, during, and after my incarceration. It is written without malice or prejudices, but with a profound feeling of hope that no other American in the armed forces of the United States, or any other nation for that matter, will ever have to endure the pain, suffering, and humiliation as a Prisoner of War. I'm a humble survivor striving to put past experiences and nightmares behind me while enjoying my freedom in the company of my lovely and caring wife and our four wonderful children. It’s been many years, many sleepless nights, and many trips to doctors seeking medical care and attention for what I endured to ensure the freedom and security of my family, and families of all free nations. I am here…… putting my life in order, while wondering how to deal with the disturbing world news confronting me whenever I turn on the television set. Sadly, I think of the “freedom” George Washington, the father of our country, had envisioned for this new nation, the “freedom” dreams of President John F. Kennedy and the startling awaking of the American people following his assassination. Add to this the hate groups, the left wingers, the right wingers, Cuba, Panama, Vietnam, Cyprus, and I ask myself, "WHY? WHY?” When will the American people rise from their placid, quick-to-forget, "I pay my taxes" attitude and realize the possible fate that awaits our country. “They are over there, and we are over here. Why bother?” As I regress into the events of my childhood, I am reminded of young men and women longing to come to terms with themselves and their future, for I was one of them. However, I am encouraged and drawn to the “courage” exemplified by these young service men and women who valiantly face and honorably prevail over adversities in the services of their country. With profound respect and admiration, I proudly salute the honor and dignity of my fellow comrades who survived and those who died in the Korean War. And, I humbly dedicate this story to my family, to all former Korean Prisoners of War and their loved ones, and especially to all those with whom I have had personal contact and the honor of serving. I personally want to “acknowledge” and thank all of my friends and buddies who shared their stories and experiences with me. Also a special acknowledgment and thanks to my good friend and buddy Benjamin Comeau for giving me copies of his drawings and a copy of the Military Script with all of our names from Company Seven, Camp One/Three, Ch’angsong, North Korea, from October 1951 to August 1952. Chapter 1 - FJ ChapmanI am Franklin Jack Chapman, a patriotic American who survived incarceration as a Prisoner of War for 33 months during the Korean War. I grew up in the middle and far western half of the United States, and I’m especially proud and respectful of my Cherokee Indian heritage, my nationality as an American, my family customs, traditions, kinship, and above all, the freedom enjoyed by all Americans. I was born in the Flat Rock area of Mazie, a township in Mayes County, Oklahoma, a short distance from the Grand River, in the house of my mother’s father on January 24, 1933. I never knew any of my maternal grandparents, except that they were of Cherokee Indian stock. My grandmother had died on January 9, 1929, and my grandfather had died 11 days before my first birthday. As for my father’s side, I can only relate what I have been told over the years, since I never really knew him or what he was like. My mother never spoke of him. My mother had remarried, and by the time we moved to Muskogee, Oklahoma, in 1939, there were three of us boys. However, due to misunderstandings and a faltering relationship with my stepfather, I decided to take control of my life. I had dropped out of high school at the early age of 14. By the time I was nearing 15 years old, I had already traveled (by myself) from Oklahoma to California, then to Washington, back to Oklahoma, then to Michigan and back to Oklahoma. At age 15, the only work I could find was gathering pecans and walnuts, and working the cotton and hay fields. During this period, I lived with my mother’s brothers and worked at odd jobs. Then in the summer of 1948, I worked in the onion fields while staying with my uncle in Michigan. It was here I had decided, “This is not the life for me!” With my meager savings, I bought a bus ticket to Oklahoma, where I had a couple of uncles and an aunt who lived there. While there I tried to get a job working on the railroad. I had heard the railroad was looking for help around Oklahoma City. So with little more then a few dollars in my pocket, I took off for Oklahoma City in search of a job on the railroad. It was late in the afternoon when I finally found the Railroad Foreman’s office. When I entered the office, I told him I was 18 years old and needed a job. The foreman took one look at me and said, “You can stay the night here, but tomorrow morning, I don’t want to see you around.” He took me to the mess car where I was fed, then showed me the sleeper car where I stayed until morning. When I awoke, I didn’t really know what I was going to do! I had less then a dollar in my pocket. I picked up my bag, which contained a change of clothing and my Bible, and started hitchhiking to Tulsa, Oklahoma. Around lunchtime, I found a store and bought some bread and a soft drink. This left me with about fifty cents. Hitchhiking was bad, so I kept walking. Occasionally someone would stop and give me a ride, but only until they turned off of the main highway. It was well after dark when I saw a light in the distance and headed for it. It turned out to be farmhouse. When I knocked on the door, the man of the house came to the door. He asked what I wanted. I explained my situation, was given some water, and told to be on my way. The next afternoon I found myself at the outskirts of Tulsa, Oklahoma, where to my dismay, the police stopped me. They searched my bag and couldn’t find anything but my change of clothing and my Bible. Without further comment, they let me go and I was on my way. I don’t recall where I stayed that night. Somehow, on the next day, I had made it back to Muskogee, Oklahoma. My mother fixed me a meal, and because I didn’t want to hang around the house with my stepfather, I left. A couple of days later, I was hitchhiking to the place of my mother’s uncle, where I worked for about a couple of weeks. Aunt Mary and my uncle had several children and fortunately for me, considered me as one of their own. Aunt Mary had nursed me when I was a baby. She was a full-blooded Cherokee Indian, petite and beautiful, and not a mean bone in her body. When I left their home, I went to the nearest Naval Recruiting Office, wanting to enlist in the Marines or the Navy. I completed all the necessary paper work, putting my age down as 17, although I was only 15, with my address being that of my uncle and aunt in Tulsa, Oklahoma. The Recruiting Officer asked me to come back the next day. When I returned, he informed me I had lied about my age, and therefore, I could not be accepted, but to come back when I was old enough. I was getting desperate and really wanted to find a decent job. The only thing I came up with was a job setting pins in a bowling alley. It wasn’t much! I worked at setting pins from the moment the lanes opened until they closed it. Since the manager liked the way I worked, he made sure I was given the best bowlers. After a month or so of working at this job, I decided to try the Army Air Force. Three days after my 16th birthday, I went to the Army Recruiting Office. Since I didn’t have a birth certificate, all I would need was for someone to sign for me, and I was in! At the same time, several young men were being recruited into the Army and several others were being drafted. I was the only one who had signed up for the Army Air Force. However, during our physical examination, several Army candidates talked me into joining the Army with them. Everything went well. I didn’t have any problems getting on board. Perhaps it was because the Recruiting Officer was too busy processing the other men being drafted into the Army that he totally forgot about me. I was in! I had a new home and had taken my first step toward total independence with a decent job. I was a soldier on my way to see the world, to seek out what fate had in store for me. I was shipped off to Camp Chaffee, Arkansas for 8 weeks of Basic Training, which turned out to be a breeze. During my first month there, I was selected as Soldier of the Week. Following Basic Training, I was assigned to the 14th RCT, Heavy Weapons Company (4.2 Mortar) at Camp Carson, Colorado, just outside of Colorado Springs. In the platoon I was assigned to, there were two veteran soldiers who served in WWII. One was from Arkansas and the other from Mississippi. They were darn sharp too! One day the Sergeant from Mississippi called me aside and wanted to know my age. I replied without hesitating, “SEVENTEEN SIR!” He said, “You sure look awfully young for seventeen. Are you sure?” “YES SIR!” I replied. Nothing else was ever mentioned of my age again, until I went to Korea. At Camp Carson I was selected as Soldier of the Month for our Company, and for that honor, I was assigned duty as the Colonel’s Orderly for a day. During my tour there, I faced fear several times. I recall being assigned guard duty for prisoners on work detail, and at the Stockade. The prisoners were much older than I, and because of this and how young I looked, I felt intimidated and afraid whenever I performed this duty. One night, one of the prisoners tried to escape and was fired upon by another guard. This frightened me because it could have easily been me firing that shot. I always felt real glad whenever my tour of guard duty was over. While stationed at Camp Carson, I received training in 4.2 mortar operations, cross country skiing, rock climbing, track vehicle operations, and spent two months of training in Alaska. Upon returning to Camp Carson from Alaska, my platoon was further assigned temporary duty at Camp McCoy, Wisconsin, where I received orders for duty in Japan. Upon arriving in Japan, I was assigned to Company D (Dog), 31st Infantry Regiment. And, little did I know my next stop would be a war in Korea, where my rites of passage for bravery would be tested while incarcerated as a Prisoner of War for 32 months and 20 days! Chapter 2 - Battleground KoreaBefore the war broke out in mid-1950, few people in the Western World either knew, or cared to know, about Korea or its people. Under the impact of war, knowledge became essential. Old books on the subject were dusted and new ones were quickly rushed to the printers. Maps of Korea filled the newspapers and slowly some of the strange sounding names became familiar to the man on the street. The candle of indifference was replaced by the searchlight of interest as Korean geography and history took on new importance. Korea shares a long, common frontier with Manchuria along the Yalu and Tumen Rivers and touches the Soviet Union on the mouth of the Tumen, see Figure 1 below. From the northernmost bend of the Tumen, Korea extends some 600 miles to the southern tip of the peninsula with a width varying from slightly over 100 miles at the waist to approximately 220 miles at its broadest part. The dominant feature of the topography is the mountainous Taebaek chain covering northeastern Korea and running south along the eastern coast. The mountain slopes dip sharply down to the sea in the east, but are gentler in the west. Roads, railroads, and the communications network follow the valleys and mountain passes in the broken terrain. Korea is an agricultural country raising most of its dry crops in the north and the bulk of its rice in the south. The majority of its heavy industry and hydroelectric development is located in the north. Average precipitation and mean temperatures are similar to those in the Middle Atlantic States of the United States, but the winters are much colder and over 80 percent of the rainfall is concentrated in the seven months between April and October. Floods are fairly frequent during this period. With such a long salt-water frontier, fishing villages dot the cost of Korea. Ironically, the best ports are on the southern and western coasts, where tidal variations are more extreme. There are few good harbors on the Sea of Japan, which has a tidal range of only about three feet. Located at the strategic crossroads of East Asia, Korea has had a long and checkered history. For many centuries the peninsula experienced a series of petty wars between rival powers seeking to establish hegemony. Finally, during the seventh century, the kingdom of Silla managed with Chinese aid to gain control of most of Korea. The influence of Chinese civilization at this time brought about Korean acceptance of the Confucian system of social relationships and left a lasting imprint upon Korean ethics, morals, arts, and literature. Despite invasions from barbarian hordes during succeeding centuries, on the whole, Korea remained faithful to its father-son relationship with China. Chapter 3 - The Invasion Of South KoreaOn June 25, 1950, the news came of a Communist aggression from North Korea aimed at the Republic of South Korea, a young struggling democracy formed after World War II. Then, more news followed… The North Koreans had invaded South Korea and overran the City of Seoul like a horde of locusts, and were pushing further south toward Pusan. Korea was a country only a few of us (young soldiers) had heard of, much less discussed. So not really knowing what it all meant, we briefly talked about the situation and proclaimed our hope and belief that the United Nations action would settle the matter. There were rumors that the United States forces were to be deployed to deal with the aggression, before the United Nations could begin their deliberations. Soon there were speculations on which units would do what, causing Commanders to inventory equipment on hand and attempt to make up the shortages in manpower which, they learned, was not possible in the peacetime United States Far East Command. Armed with Soviet weapons, the North Korea People’s Army (NKPA) forces had invaded South Korea. Six days later, a battalion of the United States 24th Infantry Division was rushed to South Korea from Japan, and readily engaged the enemy on the outskirts of Seoul. At the start of the Korean War, all US Army units were under manned. The 7th Infantry Division was stripped of all but a few trained men to reinforce units going to the Pusan perimeter. More then half of the units were replacements just in from the States, and most of them came from the 3rd Army stationed at Fort Benning, Georgia. The U.S. military was not ready for a ground war. After World War II and the debut of the atomic bomb, the Army and Marine Corps were rapidly demobilized. Equipment budgets were slashed. In its new role as a peacekeeping force, the Army of June 1950 was ill-equipped, under-strength, and poorly trained. US Forces in Japan is MobilizedWithin weeks, United States forces in Japan were being reinforced with South Korean Army troops to make up for the shortage of manpower in our units. When the Korean War started, my Company had about 60 men and half of our reinforcements were South Koreans. The South Koreans were hard to understand, so we needed an interpreter for everything, but they were good people. Then news came describing how the initial American reinforcements in Korea were being virtually annihilated, and more were needed. The 7th Infantry Division, with its three regimental combat teams and support units (which my unit, "The Polar Bear Regimental Combat Team" was an integral part of), was soon to be on its way to the "United Nations Police Action." Time became an important factor, as shortages of equipment, personnel, and compliance with training schedules were forgotten and assembly for shipment began. Then came the long array of convoys, their equipment and ships all being of World War II vintage. The hours of loading and getting underway were long, dismal, tiring, and nearly unbearable for the young and inexperienced troops at hand. We were then briefed on what lay ahead although our superiors had no idea what we would eventually encounter, since American forces had never before met hard-core Communist elements in battle. Shortly thereafter, my childhood memories rolled vividly before me; school years, the pledge of allegiance each morning before class, the study of American history and American patriots, and of the forward drive and greatness of our country's sovereignty. The UN Counter-OffensiveIn September 1950, the United Nations launched a powerful counter-offensive against the North Koreans. At first, the North Korea People’s Army (NKPA) moved down the Korean Peninsula with relative ease. But on Sept. 15, General MacArthur launched his brilliant amphibious landing of the X Corps at Inch'on, deep behind enemy lines. The landing of the 1st Marine Division and the Army’s 7th Infantry Division opened the door for an allied victory. The US 1st Marine Division and my unit, the 7th Infantry Division, made amphibious landings on the west coast of South Korea at Inch’on, approximately 200 miles north of Pusan, South Korea, to cut off the North Korean’s communication lines and recapture Seoul. As the United Nations Forces were 'mopping up' the southern resistance, plans were being made for another landing. This would be a back breaker landing in the North Korean heartland to isolate the North Korean units from logistical support and to force them to surrender. The X-Corps, consisting of the 7th Infantry Division and the 1st Marine Division, was to do an amphibious landing at Wonson, on the East Coast of North Korea. They would join up with the 8th Army and attack across the 38th Parallel, its main objective being North Korea’s capital city of P'Yongyang. When this proposed action was being initiated, we didn’t know the Communist Chinese was amassing its forces of hundreds of thousands of screaming people, in support of North Korea, at the Yalu River. Around the end of September, the UN Assembly authorized the crossing of the 38th Parallel. Within weeks, the North Koreans were pushed back across the 38th parallel. The map in Figure 3 shows the route taken by the Inchon Invasion Task Force of the United Nations Forces for a landing at Inchon, South Korea, on September 15, 1950. General Douglas MacArthur, Commander in Chief Far East, was the UN Forces commander. Chapter 4 - Landing At Inch’on, South Korea And On To North KoreaThe map below, Figure 3, shows my journey through South and North Korea since landing at Inch’on South Korea on September 18, 1950, until my departure from the country in 1953. The heavy black arrows on the map show the routes I took prior to my capture. The heavy red arrows show the “death marches” routes I took as a prisoner of war. I arrived in South Korea on September 15, 1950 with the Army 7th Infantry Division and 1st Marine Division by way of an amphibious landing at Inch’on, South Korea. Little resistance was encountered from the Communist forces during the landing, however, resistance from the area’s natural elements and terrain greatly impeded our every effort. Surprisingly enough, the landing and reassembling were quickly completed for most of our units, and we were rapidly on our way southward to trap the North Korean People’s Army. On or about October 5th 1950, my unit, the 7th Infantry Division assembling near Suwon, commenced its motor-march southward to the huge, overcrowded (with refugees and United Nations Army Units) city of Pusan, South Korea. We used our own trucks and some from the 8th Army and the Marines. We were ordered to take a 350 mile roundabout inland route from Suwon to Pusan (Suwon-Chungju-Kumchon-Taegu). My first real enemy engagement came in the mountainous Suwon area. After several heavy encounters, our leaders assumed the arrival of the second wave of United Nations Forces would convince the North Korean commanders to lick their wounds and high tail it back North. Eventually, the North Koreans did just that by skirting through and/or around the widely spread units of the United States and the South Korean Army, leaving behind an array of guerrilla units. On or about October 8, 1950, the Marines and 31st RCT reached Pusan. We had been in combat wearing the same clothes since landing in mid-September. The Marines and 31st RCT boarded ships for our landing further north. On or about October 10, 1950, the X-Corp’s mission was changed to advance northward instead of westward from Wonson. General Almond decided to land the 7th Infantry Division as close as possible to its axis of advance inland toward North Korea's northern border. The 7th Infantry Division would land at Iwon, North Korea, about 105 miles northeast of Wonson, North Korea, in the enemy's industrial region. Then they were to proceed north to the Yalu River, which separates North Korea from Communist China. By October 16, the 7th Infantry Division with its equipment and men had been packed aboard ships for the trip north. On or about October 27, 1950, the LSTs and ships sailed up the northern coast from Pusan to Iwon, North Korea, for the landing that was to end the United Nations Police Action in Korea and have the American GIs home for Christmas. The fleet set sail, heading north through the chilling winter waters off the eastern coast of North Korea. During the trip, we were again briefed on the "Gung Ho" American type landing of World War II. Only this time, it was supposed to be comparatively easy, with the psychological effect of a mass UN Forces landing in North Korea, to finally complete the job. The Landing at Iwon, NK, October 29, 1950.Two days after boarding the ships, we landed at Iwon, North Korea. The landing was not as difficult as the assault landing at Inch’on, South Korea. The beach was rocky and the water much colder, but the overall terrain was much kinder than our previous landing. When we landed at Iwon, the 17th Regiment charged inland to take P’ungsan, while the 31st Regiment, on the 17th’s left in the Division's center, moved northward to the left of P’ungsan. My unit, the 7th Infantry Division, headed north along the northern coast through Kilchu, to the Yalu River at Hyesanjin. Roads were non-existent in this area. We spread out, mostly on foot, into the mountains, "holding" or "advancing" in the Division's center. After moving inland, our morale was high, still believing the "Home for Christmas slogan”. However, we made a tragic mistake by spreading ourselves too thin over the northern most part of North Korea. The 3rd Battalion of the 31st encountered a few Communist Chinese Forces soldiers who fought desultory or not at all. This led our Commanding Officers and others to unwisely regard all Chinese with contempt. All of our units were moving “helter skelter” toward the Manchurian border, close behind the retreating North Korean Army. We skirted some straggling Chinese soldiers, believing our rear echelon units would make short work of them. By the end of October 1950, the US 8th Army had attacked the North Korean city of P'Yongyang. The ground troops assaulted from the south, and a parachute drop north of the city by the 187th Regimental Combat Team completed its envelopment. To all of us, the fall of P'Yongyang, the enemy's capital city, symbolized complete defeat of North Korea. Practically all organized resistance had come to an end. The North Koreans had ceased to exist as an effective fighting machine and the way seemed open to a speedy end to the hostilities. So we thought!! The Yalu RiverBy mid November, elements of the X-Corps had advanced to the Yalu River. Our instructions were, “Under no circumstances are we to cross the Yalu River.” From mid November on, canteens remained frozen, so we had to melt snow for water and instant coffee when a fire could be built. As the bitter cold North Korean winter moved upon us, we were ordered not to cross into Manchuria, pending negotiations that would end the "Police Action." It was felt the North Koreans had learned their lesson, and we could still be home for Christmas. However, in conjunction with talks of the forth-coming negotiations that would supposedly end the police action, we also heard rumors of a tremendous build-up of the North Korean lines bolstered by the Communist Chinese Forces (CCF). The word was, “This is just a face-saving maneuver by the CCF elements after having recently been driven northward by the United Nations Forces. They would not dare to try it again, but would instead, negotiate!” We were in for a rude awakening!! Our daily patrols began to report an estimated one million CCF soldiers were massing along the opposing lines. They seemed to have the manpower, but not enough weapons to go around. These hard-core communist elements had also been thoroughly brainwashed into thinking their first weapons would come from captured stocks taken from United Nations Forces. A few days before Thanksgiving Day, our Marines had engaged the Chinese at Sudong. They had taken some prisoners and presented them to the higher-ups as proof of Chinese intervention in the war. South Korean troops had also taken Chinese prisoners but still, the higher-ups denied the Chinese were in Korea in full force. The 1st Battalion, 31st Infantry Regiment (with Charlie Company of the 57th Field Artillery attached), was ordered to continue its present mission from the Yalu River, south to the Pukch’ong area. The 2nd Battalion was ordered to close in without delay and be prepared to attack north on order. Thanksgiving, Pukch’ong, NKAfter spending a few days on the Yalu River at Hyesanjin, NK, we headed back south through Kapson and P’ungsan to Pukch’ong, just south of Iwon. We arrived there on or about November 21, 1950, just before Thanksgiving. On Thursday, November 23, 1950 (Thanksgiving Day), we were treated to a turkey dinner with all the trimmings. A day or so after Thanksgiving Day, my unit, a Heavy Weapons Platoon from Delta Company, was assigned to Captain Charles Peckham's Company B (Baker Company), 31st Infantry Regiment. Our orders were to advance to the Changjin (Chosin) Reservoir. What we didn’t know was the Chinese, in full force, had crossed the Manchurian border and was allowing the UN Forces to move deeper into North Korea before springing their trap. Hamhung, November 25-28, 1950On our way to the Chosin Reservoir, we arrived at Hamhung, NK, sometime around midnight, November 25. We remained at Hamhung, until around 12 p.m., November 28, getting supplies, replacement equipment, and waiting for winter clothing that had been ordered for us. Then we continued northward to the 1st Marine Division’s Command Post, which was located at Koto-ri, a few miles south of the Chosin Reservoir. Our orders were to open up the road to Koto-ri and fight our way in a leap-frog fashion to Hagaru. Somehow, the supply of winter clothing that had been ordered for us had not arrived before we left Hamhung. We were not prepared for the icy weather that had already laid a mantle of frost on the ground, and capped the highest peaks with snow. At dusk, the temperature dropped abruptly for the second day in a row, to a numbing 30 degrees below zero. I had on two pairs of pants, two shirts, a field jacket, and no overcoat, and I was freezing. Man was it cold! I had received training at Camp Hale, near Leadville, Colorado at the old home of the 10th Mountain Division where I learned to ski and rock climbing. During the winter of 1949-1950, I was on maneuvers in Alaska where we slept outside, and most of our time was spent in the field, skiing and snowshoeing. But, we were equipped with the appropriate winter clothing and gear. The only other time I can remember being so cold was when we made a stop in Great Falls, Montana, when returning from Alaska. The temperature, with wind chill factor, was around 50 below zero and it was cold!! Thanks to my cold weather training in Colorado and Alaska, I had an advantage over many of my fellow soldiers. If we had adequate winter clothing and gear, just maybe, we would not have mind the cold so much. Boy, we were cold, cold, cold!! It was something!!! Needless to say, we had started our mission to Koto-ri and the Chosin Reservoir without proper winter clothing and equipment. Our C-rations were frozen! We didn’t stop long enough to thaw them out. The extreme cold made leather gloves so stiff that fingers wouldn’t and couldn’t bend, and here’s an important fact, “You can’t load and shoot a weapon with gloves that won’t bend!” I wore the wool glove inserts without the leather shell. Otherwise, my hands would freeze to the metal of my weapon and ammunition. Through it all, we kept on moving to the 1st Marine Division’s Command Post at Koto-ri. Chapter 5 - The Chinese Communist Forces Raises Its HeadOn November 27th, the first of many Chinese attacks occurred in and around the reservoir. The Chinese had thrown seven (7) Divisions around the reservoir in preparation for the battle at Changjin (Chosin) Reservoir, one of the greatest epics of the Korean War (Figure 5 below). They had also erected 11 roadblocks between Koto-ri and Hagaru, and most of the bridges were blown, damaged, or destroyed. With the coming of darkness and intense cold, thousands of Chinese began to move over the crusted snow. Three (3) Chinese Divisions closed in on two regiments of our Marines. Two (2) Divisions struck Yudam-ni, and the third slipped south to cut off the 14-mile long route leading southeast to Hagaru. Toktong PassToktong Pass, located approximately six (6) miles southeast of Yudam-ni, was the most vital terrain along the 14-mile route. As darkness fell on November 27, the Commanding Officer of Fox Company, 7th Marines, ordered his men to dig in before erecting any tents. This they completed. The perimeter remained quiet well past midnight. Then around 2:30 a.m., November 28, all hell broke loose as the Chinese struck from three directions! In their first assault from the high ground to the North, the enemy swarmed the forward position of a Marine platoon. The Lieutenant in charge had deployed his men with two squads forward and one slightly to the rear in a supporting position. In the initial onslaught, 15 Marines were killed and nine were wounded. The eight remaining Marines fell back slightly. When it was over, a head count revealed three Marines missing. They were Corporal Wayne A. Pickett, and Privates First Class Robert L. Batdorff and Daniel D. Yesko. (Source: 1st Provisional Historical Platoon Interviews, April 17 1951, No.1, G-3. Historical Branch Archives, Headquarters, US Marine Corp 1st Marine Division, Casualty Bulletin 89-50, December 27, 1950). On the 175th anniversary of the founding of the Marine Corps, the 7th Marine Regiment had moved its Command Post 12 miles up the narrow mountain road to the little town of Koto-ri, an important road junction on a high plateau. The Command Post was established a little over eight miles from the vital hydroelectric power plants on the Chosin Reservoir, as fire fights were going on with Communist Chinese Forces in the hills less than 1500 yards away. Phil McCoy, USMCLater, my neighbor Phil McCoy of the 1st Marine Division, Field Communications, stated, “Someone must have been praying for me." This was the way Phil explained why he wasn't injured when the enemy had cut him off with part of his unit. "Someone must have done a lot of praying for me because I sure had a lot of close calls." Phil was a Reservist, called back to active duty on August 9th, 1950. As we talked for a long while, Phil stated he didn't think they were going to make it back to Hamhung. “A lot of the guys didn't get back, and I was scared out of my wits.” he said. He also said, “I used to think it got cold at home (Kent, Washington), but when we were in North Korea, the temperature was around 28 degrees below zero, and we slept outside! When you heated coffee, you had to drink it right away or it would turn into a block of ice.” Phil’s feet were frostbitten. Chapter 6 - Arrival At The 1st Marine Division Command Post, Koto-RiAfter leaving Hamhung, we arrived at Koto-ri during the evening of November 28. We were bone tired, nervous, and tried to get some rest in the freezing cold without much success. Throughout the evening, there was gunfire off in the distance. Formation of Task Force DrysdaleDuring the day of November 28, 1950, General Oliver P. Smith ordered Colonel Lewis Puller, at Koto-ri, to send him desperately needed reinforcements to hold Hagaru-ri. General Smith wanted reinforcements, although it meant they would suffer heavy casualties in reaching Hagaru-ri Colonel Puller's 1st Marines, who still had the job of opening the road and reinforcing Hagaru-ri, also had their hands full defending the Koto-ri perimeter.

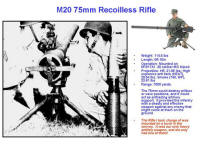

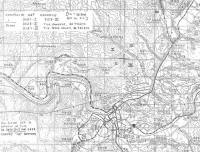

Colonel Puller could only spare one Rifle Company to reinforce the Marines to the north. Clearly this was insufficient, particularly in light of the action being fought by Dog and Fox Companies that same day! The only solution was to form a composite unit with whatever forces that could be pulled together. On November 28, 1950, the British 41st Independent Commando Royal Marines Battalion had also just arrived at Koto-ri to operate under the X Corp. When transportation and equipment had been found, the initial intention was for it to serve as a reconnaissance group. Although the unit was new to Korea and had not seen any action as yet, there was a matter of urgency to reinforce the Hagaru-ri perimeter with every available man. The British unit’s commander, Lieutenant Colonel Douglas B. Drysdale, was ordered to command the composite unit which was named Task Force Drysdale. The mission of Task Force Drysdale was to cut through the Communist Chinese Forces along the 10-14 miles road stretching between Koto-ri and Hagaru-ri. The Task Force numbered around 900 men with armor support. Among others, this included 235 members of the Royal Marines, about 205 US Marines, of Captain Carl Sitter's "G" Company, some 190 soldiers of Captain Peckham's Baker Company, 31st RCT, and about 82 U.S. Marines (clerks, truck drivers, military policemen and several US Navy corpsmen attached to the 1st Marine Division). In all, the Task Force would consist of personnel from 10 different organizations. On November 29, 1950, my Heavy Weapons Platoon, Dog Company, 31st Infantry Regiment, commanded by Lieutenant White our Platoon Leader, and attached to Captain Charles Peckham, Commander of Baker Company, 31st Infantry, was made part of Task Force Drysdale. There was no time to feed the men before we started our journey toward Hagaru-ri. After starting the move north, the Task Force was reinforced with 29 tanks, 76 vehicles and trailers, and 287 Marines from different Marine units. Their arrival increased the size of the Task Force to nearly that of a Battalion. The official Marine Corps history of the operation, accounts for approximately 922 men plus vehicles, trailers, and tanks. However, in spite of its impressive numbers, the heterogeneous make-up of the unit rendered the Task Force ineffective as a fighting organization. This fact soon became evident at Hell’s Fire Valley. Hell Fire Valley"Hell Fire Valley" was the name given by Colonel Drysdale to the scene of the all-night battle between the Chinese and more than half of Task Force Drysdale on November 29, 1950. In the confusion along the road, roughly 400 members of Task Force Drysdale were left stranded and out of radio contact in Hell Fire Valley and completely surrounded by vastly numerically superior Chinese forces. The valley was about one mile long, covered with a frozen crust of snow and offering very little cover. It provided a convenient approach to the rear, with the Communists having the advantage, since they were entrenched on the upper regions of the precipitous slope. The higher ground rose sharply on the right side of the road, a railroad to our right was infested with Chinese soldiers, while on the left a frozen creek wound through a field several hundred yards wide, bordered by the Changjin River, the Communists were dug in, and there was a mountain to cross. About 50 to 100 yards ahead of us was what was left of Colonel Drysdale's 41st British Commandos, getting cut to pieces. They withdrew to our position sometime around 2000 hours (8 p.m.). The whistles, bugles, and battle yells alerted us to be ready for the mass of Chinese Communists forces that spilled out of the night. The screeching blasts of their damn whistles and bugles made our flesh crawl, as the sound reverberated through the chilled night air. After several minutes, the sound of gunfire, bugles and whistles would die down and stop. The map below, Figure 7, illustrates the battle chronology of events that took place in the vicinity of the Chosin Reservoir, including the area of Hell Fire Valley. The Chinese Communists were very clever. They were well trained and had perfect discipline. They enjoyed the comfort of the darkness, and during this time, they would crawl in close and then, with the sounds of the damn whistles and the blaring of bugles, the night was suddenly shattered. The night was in turmoil, broken only by the sounds of bugles, loud blasts of whistles, and then the battle yells at the onslaught of the attack. For what seemed like an eternity, a death-like silence hovered over the bitter cold darkness. We listened and waited. Suddenly the eerie sounds of the bugles and whistles could be heard again, only this time much closer. We gripped our weapons, pointing them into the darkness that cloaked everything. Mortar rounds and grenades slammed into the ground close by, spraying a shower of shrapnel over us. Here we were, the United States and United Nations Forces getting the hell kicked out of us, running out of ammunition, with malfunctioning weapons caused by the extreme cold, and about half of our men either dead or seriously wounded, while wave after wave of Chinese Communist soldiers, screaming and blowing their damn bugles and whistles, descended upon us! The killing was so savage!! The Chinese had to climb over the bodies of their own men to continue their onslaught. In addition to our small arms (rifles, carbine, and pistols) and some hand grenades, we had no weapon larger than one 75mm Recoilless Rifle. What 60 and 80mm mortars we had, were out of ammunition. We were nearly out of ammunition and, because of darkness, had no air support. You've got to understand what it feels like to be in combat with your ammunition nearly gone, or with a weapon that doesn't work! Among other thoughts of anxiety and apprehension, the feeling is ……. total helplessness! We would shoot down a whole wave of them buggers, and another wave would be right behind. They kept coming, stopping only to pick up the weapons of those who had fallen, to continue their charge like the first wave. It seemed like this went on forever, and ever, and ever! The onslaught was horrifying………it was HELL! There were so many of them! Chapter 7 - The Battle At Changjin (Chosin) ReservoirThe Battle at Changjin (Chosin) Reservoir was considered one of the greatest epics of the war in Korea. The place was inhospitable, even for the battle-tested men of the 1st Marine Division and the Army's 7th Infantry Division, some of whom had fought through the worst of World War II.

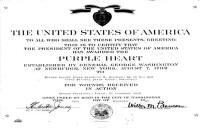

It was here that we met the might of the Chinese Communist who swarmed upon the UN Forces like hordes of ants attracted to sugar! They were well trained and battle hardened in guerrilla warfare, and carried none of the baggage of a modern army. They were masters of concealment who moved and fought only by night. Their working day began about 7pm, wearing thick, padded, green or white uniforms, caps with a red star, carrying a personal weapon, grenades, 80 rounds of ammunition, a few sticks of grenades, spare foot rags, sewing kit and a week's rations of fish, rice and tea. They would march until about 3 a.m., and then prepared camouflaged positions for the day. To determine routes for the next night’s march, scout units moved during daylight, and they were ordered, under penalty of death, to freeze motionless if they heard aircraft. Their only heavy weapons were mortars, but they made up for that with increasingly vast numbers of people in their forces. It was remarkable how the Chinese could keep their numbers and activities concealed from the UN Forces. Even our air power couldn’t discover the large Chinese forces hidden in the mountains of North Korea. Many of the bridges at the Manchurian border had been blown up, but this mattered little to the Chinese because, when the Yalu River froze, they just walked across! And, the Yalu River was frozen solid! They were dressed in quilt padded uniforms with an overcoat, and wore padded tennis shoes for footwear. I don’t recall ever seeing any of the soldiers wearing gloves. The Chinese ambushed Task Force Drysdale about halfway to Hagaru-ri, in what became known as "Hell Fire Valley". We were outrageously outnumbered, and it was only a short time before the wave upon wave of Communist Chinese Forces had cut us to pieces! AmbushedIt was 0945 Wednesday morning, November 29, 1950. The mist was low over the snow-covered bitter cold countryside of Koto-ri, as the convoy of Task Force Drysdale began its move north toward Hagaru-ri. Behind the British Commandos came Baker Company, 31st Infantry. We huddled in the trucks, with our heads buried deeply in our field jackets against the biting cold. Almost immediately, we met resistance and began engaging elements of the Communist forces. At first, we didn’t hear the sharp crack of small-arms fire, but when the mortar rounds began to fall and machine guns opened up, that definitely got our attention!! A truck about one third of the way along the mile long column got hit and began to burn. The damaged truck blocked the center of the column, and Chinese small arms and mortar fire prevented its removal. We had no communications due to the distance, terrain, and other circumstances, so neither the front nor the rear of the convoy realized the center of the column had been cut off. In the center column was some British 41st Commandos, most of Baker Company, the Marine Military Police Detachment, and some Marines from service and support units. As brakes slammed and trucks skidded to a stop on the narrow icy road, a hand grenade landed in the bed of my truck near my feet. Without thinking, I grabbed the grenade and tossed it out of the truck toward the railroad. Almost at the same time, we all jumped from the vehicles and dove for cover in the ditch on the side of the road. What we thought was a ditch, was just a low place between the railroad embankment on one side and the roadbed on the other. The Chinese began lobbing a steady rain of mortar shells, and from the hills machine guns raked the ditch banks with gun fire. They didn’t come in close just then. Allied aircrafts, seeing the burning truck on the road, would swoop back and forth all day long rocketing and strafing the Chinese. Then the resistance we had encountered earlier had stopped, and we mistakenly believed the Chinese had withdrawn and we were in the clear. The head of the column, which included the British 41st Commandos, a Marine rifle company, and several tanks, pushed their way on to Hagaru-ri. As soon as darkness put an end to the Marine air strikes, all hell broke loose! The Chinese became increasingly bold and the struggle began in earnest. They started firing again, just enough to keep us on our toes. For several hours there was no attempt from them to get within grenade throwing distance. We fought back the attacks, only glimpsing the enemy briefly by the light of flares and gun flashes. The center portion of the Task Force came under increasingly heavy enemy fire. The Chinese had succeeded in splitting the Task Forces even more, reducing it to one large perimeter and three small sections. Casualties continued to mount. Bodies were stacked all around the hastily formed perimeter. And, freezing temperatures dipping to 20 degrees below zero threatened to take an even greater toll. We attempted to turn our vehicles around and head back to Koto-ri, but this attempt was unsuccessful, the convoy section I was in was cut off from both Koto-ri and Hagaru-ri. In addition to our rifles, carbines, pistols, submachine guns, and some hand grenades, we had one 75mm Recoilless Rifle mounted on a truck. It was a clear, bright, starlit night, and the truck burning on the road provided more light. We could see the Chinese, by the hundreds, coming across the snow. They had our convoy zeroed in. The only cover we had were our vehicles and the shallow ditches, on either side of the road and the narrow railway, for protection from rifle fire and grenades. The Chinese didn’t bother to creep or crawl, they just came on, standing and walking. And from the shallow ditches, we kept on firing, and firing, and firing!! During the early evening of November 29, I received my first of seven wounds. My left arm was hit with shrapnel, but it wasn’t too serious. After it was cared for at the Aid Station, I refused to return back to Koto-ri. Instead, I returned to my squad and shortly thereafter, was wounded with shrapnel to my right leg. Once again, I returned to the Aid Station, only to find the Corpsmen busy treating more seriously wounded men, so I returned to my position. The fighting was getting pretty fierce. One of the men standing next to me got a bullet in the forehead. The bullet went through his skull and embedded itself in his helmet. Manning the 75mm Recoilless RifleAround 2100 hours, November 29, the gunner of the 75mm Recoilless Rifle, a Sergeant from my squad, jumped down from the weapon, got down on his hands and knees in front of the vehicle and started praying. He refused a direct order from Captain Peckham, Commanding Officer, Baker Company, to reassume his position. Captain Peckham insisted, and finally told the Sergeant he was going to be put in for a court martial for refusing a direct order….. But still, the Sergeant refused! Knowing the importance of the 75mm Recoilless Rifle (Figure 5 below) to his Company’s firepower, Captain Peckham immediately looked for someone else to take over the gunner’s position, but was unsuccessful. So, I told him I would take over the weapon. While manning the rifle, I sustained shrapnel wounds to my left leg, and bullet wounds in my right arm and right leg. This was in addition to the wounds I received earlier. Undaunted, I and what was left of my crew continued to fire the rifle at any enemy machine gun/mortar flashes, until I was shot in the forehead and the gun put out of action. I had just finished reloading the rifle when I was hit in the head, above the right eye, and I didn’t get a chance to fire it. Sergeant Charles Hrobak from Baker Company told me that it was the last 75mm round. It was about two days after being captured when I noticed a hole in my field jacket pocket. I had a pack of Philip Morris cigarettes (C-ration cigarettes from World War II) in the left breast pocket of my field jacket. When I pulled out the cigarette pack, I found a Chinese burp gun bullet in the pack. This pack of C-ration cigarettes had saved my life! Of the 900 men of Task Force Drysdale, approximately 300 arrived at Hagaru-ri, 300 were killed or wounded and about 135 were taken prisoner, with the rest making it back to Koto-ri. Seventy-five of the 141 vehicles were also destroyed. Heroics of the 75mm Rifle CrewDuring my research of the battle at Chosin Reservoir, I found the following excerpts citing the heroic actions and valor of the Army crew manning the 75mm Recoilless Rifle. The following statement was made by Major John N. McLaughlin, on 5 November 1956, in a book entitled “The Chosin Reservoir Campaign, US Marine Operations in Korea” by Lynn Montross and Captain Nicholas A.Canzona, USMC.

The following is an excerpt from a book, entitled “Breakout (The Chosin Reservoir Campaign), Korea 1950,” by Martin Russ. Martin Russ earned a Purple Heart when he served with the Marines in Korea.