|

We need your help to keep the KWE online. Jim Doppelhammer, our longtime webhost, has passed away and his webserver will go offline

in 2025. The entire KWE website must be migrated to a modern server platform

before then. If you value this resource and want to honor our veterans by keeping their stories online

after 2024, please donate now.

For more information, click here.

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| Back to "Memoirs" Index page | |||||||||||||||

|

|

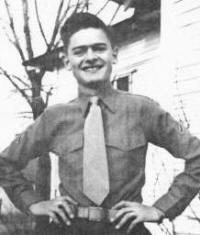

Robert Bailie Cox, Jr.Olympia, Washington- "My idea of a hero is someone who puts himself out there in a dangerous circumstance to help others and does it without regard of himself. I have seen many people do that. My hero of the Korean War is my brother John. He did a lot of rescues in minefields and in the trenches. He was wounded twice and carried shrapnel to his deathbed fifty years later." - Bob Cox

|

||||||||||||||

Memoir Contents:

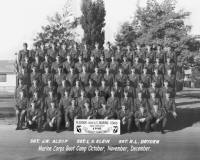

Pre-MilitaryMy name is Robert Bailie Cox, Jr. I was born on October 3, 1931 in Boise, Idaho, a son of Robert Bailie Sr. and Edith Martha Williams Cox. I have brothers Steven and John and sisters Lois and Elaine. Steven was five years older than me, John was 14 months younger, Lois was three years younger, and Elaine was seven years younger than me. Our father was a sign painter/commercial artist. Mother was a registered nurse and floor supervisor at the County Hospital. During the Depression she was a nurse midwife. I attended all twelve school years in the town of Twin Falls, Idaho, graduating in 1950. From the age of 12 to 18, I had morning paper routes. In high school I had "stock-boy" jobs at Kings 5 & 10 Cent store and J.C. Penney's Department Store. In my senior year I was a Corporal in the National Guard and worked after school at the Armory doing jobs that needed to be done--cleaning up, cleaning weapons, and keeping the place looking good. I was a Boy Scout but only got to the rank of First Class Scout. I left the scouting movement after I had a misunderstanding with the scoutmaster (my fault). I was in school during World War II. My older brother Steve was a medical corpsman in the Navy and served with the Marines at the landings at Enewetok and Kwagelein. At school we had scrap drives (iron, aluminum, copper, lead, and paper). Everyone was involved in some group activity and some of us freelanced by collecting scrap and selling it to dealers for pocket change. Twin Falls, Idaho was a farm community. I found that doing farm labor when I had spare time was a profitable thing to do. I got top wages and there was not much competition because the others were all off to war. I did a thing called "contracting" (working by myself). I contracted to do so many acres at a set price. I worked alone and without supervision and, if I did not goof off, I made very good money for a 14-year old. By the time I was 16, men came home from the war and farm laborers were imported from Mexico who worked for cheaper wages than me, so it was back to the dime store at 50 cents an hour. Rite of PassageI joined the Marine Corps on October 26, 1950. They needed Marines and I qualified. My parents left the decision to join up to me, but my father said I had to finish high school before I left home. Enlisting in the Marines was my rite of passage. My best friend, Donald Eberhart, tried to join with me, but he was dyslexic and could not pass the tests. I went by railroad from Salt Lake City to the Marine Corps Recruit Depot (MCRD) in San Diego, California. No one that I knew went with me. MCRD was on a sandy area west of downtown San Diego. It was a "short-sleeve" place even in the winter. When we arrived, we were collected at the San Diego railway depot, bussed to the base, and again put with another group and taken to a barracks to wait for several hours until the barracks was almost full. Then we were taken to supper. We were bedded down that night around 9 p.m. It was a week before we started training, so we were collected into the Casual Company until then. When it was time, we were assigned in alphabetical order to a platoon. There were three platoons formed, and mine was roughly the first one third of the alphabet. The platoon to which I was assigned was Platoon No. 88-50, First Recruit Training Battalion. Sergeant Dryden is the only one of three drill instructors (DIs) that I remember. He was a veteran of the Iwo Jima landing. He was not the senior DI. Boot camp was eight weeks long and consisted primarily of close order drill, physical fitness, how to take care of gear, awareness of sexually transmitted diseases, mess duty, learning to shoot, and taking care of our rifles. Non-classroom training was close order drill and physical training. Classroom training was everything else except mess duty. Church was offered but I only went once because the DI railed away at "sissies" who went to church. Our days were regimented 24 hours a day. We (all 72 of us) were together 14 hours a day. Sergeant Dryden woke us up in the mornings by throwing the garbage can the length of the barracks. Other DIs blew a whistle. We marched to and from every meal. (I was fed well in boot camp. I gained 17 pounds in eight weeks. We were served very good meals that were high in protein and carbohydrates.) We had to get permission to do anything at all. Personal care was stressed and everyone showered every day. We didn't have any free time until the fifth week, when we were transferred to the rifle range. One of the most important things we learned was to never depend on anyone doing for us what we ourselves forgot to do or didn't have time to do. Personally, I think Dryden was drunk when he woke us up in the middle of the night one time while we were at the rifle range. We were awakened at 2:00 a.m. and marched around the camp in the dark and over a very steep grade where several members of my platoon injured ankles. One guy broke his leg. After about three hours, we were taken back to the barracks for an hour's sleep. At daybreak we were back in formation as if nothing ever happened. Dryden reeked of booze. The DIs were really tough task-maskers. Everything had to be perfect. We were the best platoon around. The DI was probably the meanest, nastiest, most terrible person one can think of, but we needed someone who would be hard on us. We were all earmarked for grunt status. I remember that one time I was sloppy in rifle drill. Dryden took my rifle and used the butt-end of the stock to hit me very hard in the chest. I had to repeat the drill movement 100 times. The second time I was disciplined, I was caught eating a candy bar and was forced to do 100 pushups. These were the only mistakes I got caught at. We were all treated the same--just the mistakes were different for most of us. Only one person was repeatedly disciplined. He was slow mentally and was a target for the DI. Most of the discipline was on an individual basis. Only the late night march was group discipline. We were trained to work together as a team. If some one person made a mistake, the DI yelled at us all. Every day of boot camp I was sorry that I had joined the Marine Corps, but we were really good Marines--and we knew it! Dryden was tough on us, but he knew how to get the job done. No one in our platoon was killed in Korea. I am sure that he would be glad to know that. The only "fun" we had in boot camp was probably making fun of the former service types, reserves and national guardsmen. We had one black--a guy named Evans from Texas. He was one of us. We liked all of our platoon. Learning to shoot a rifle well was the hardest thing about boot camp for me. I was awarded a rifle marksman medal. When boot camp was over, there was a brief graduation ceremony. Since the platoon was very large, it was shortened by about ten persons and I was not required to march in the ceremony. I guarded our barracks. We were awarded the best marching platoon. When I left boot camp, I was one of the best Marines ever made and I believed it. I was more disciplined, squared away, and proud of who I was. Advanced Infantry TrainingWhile I was in boot camp, I was selected to go to Radio Operator School. We were assigned to the Signal Battalion for communications training. The same problem that happened in San Diego happened at Camp Pendleton. They were not ready for us so they put us in a Casual Company (alphabetically, of course) to wait until others arrived and to figure out what to do with us. While in Casual we did flunky jobs such as message center runner, headquarters building clean-up, mess hall attendant, supervising some boot trainees at mess duty, and prisoner escort (running prisoners back and forth between the brig and Captain's Mast). When it became evident that there were no funds going to be allocated for communication schooling, we were all given ten days leave and transferred to Camp Pendleton for advanced infantry training.