|

||||

|

||||

Yoshiko-San - Chris Sarno Memoir |

||||

| "Within probably 15 minutes," Sarno said, "the door opened and closed, and there was a real pretty girl

standing there. Her name was Yoshiko, and she spoke good English. She said, ‘Do I pass your inspection?’ I told

her that yeah, she sure did. We were going to spend some time together." And they did. For nearly two decades

prior, Chris Sarno’s world had centered around his Catholic family and straight-laced neighborhood in a suburb of

Boston. Now, after almost four years in the Marine Corps, his knowledge of life was expanding—not just because of

his experiences during his combat tour in Korea, but also because of his experiences with the opposite sex. "Being

close to a girl and sharing everything 24/7 was an invigorating wake up call to my psyche," he admitted. "It was a

lawful business deal in Japanese social life. I was about to grow up with sharing all of me with her, and her with

me, for the first time in my young life. This was so different from the USA ways. It was a heady five days and

nights. I treated Yoshiko with awareness and dignity. She was not a love slave to me. I was a gentle guy, and her

Japanese femininity was unmatched by any other woman I had ever met before or would ever meet thereafter. I was

aware of this characteristic, and totally loved her company."

Just before the girl had entered his room, Sarno was getting ready to take a shower. "I had my uniform unbuttoned, and she asked me if I wanted to take a shower. I told her that I wanted to freshen up before we had supper at the R&R hotel, and I wanted to get my uniform cleaned. I took it off and rang for the kid to clean it, and then we went down for an afternoon shower/bath. They didn’t have individual heads in the rooms at the Oriental Hotel. Instead, they had a common shower room. I had my robe on and she had her clothes on, and we walked down to the shower. It was three o’clock in the afternoon." The American Marine and the Japanese prostitute went to the hotel’s communal bathroom. "It was huge," Sarno recalled. It was all tiled—ceilings, walls, everything—in pretty colors. The sparkling clean room was far different from the company area back in Korea. I was loving every minute of being in this new environment. Iremember that there was a huge sunken hot tub in one corner of the room, and then down on the end there were the spigots with the showers with wooden buckets. There was a special type of sponge for your body, too. I asked Yoshiko where she was going to go while I showered, and she said that she was going to be right there with me. ‘I’m going to show you what it is to have a Japanese shower,’ she told me. So I striped down and we took a shower together. She said, ‘I like your Maline body.’ I started to soap up and she said, ‘No, no, no, no. Let me do that. Let me wash your body.’ Which she did. And then in turn she wanted me to wash her body. It was a feeling like I had never had before. I had never gone through this anyway. I used the sponge, which was really cloth. It did something nice to your skin, whatever it was called. I then soaped her. She had all the in’s and out’s. You know, there was no hanky panky going on, and I didn’t even get aroused. I was suppressing it really. She looked at me and started teasing me." Yoshiko broke away from her American companion, went over to the hot tub, and went in to it. "She went in like a slick eel, but I could see the heat coming out of that water," Sarno remembered. "So I procrastinated. I was still showering when she called me over. She couldn’t pronounce my name right. ‘Clis’, she called me. I tried to correct her pronunciation, but she couldn’t say the ‘r’. She said, ‘Come over here,’ so I did. I rinsed off and was about to stick my foot in when she started screaming, ‘You’ve got soap on you.’ I asked her, ‘So what—what the hell’s the difference?’ I was clean. But she said no soap in the tub. She was teaching me Japanese stuff. I had to go over and rinse off under my feet and everything. So I went over like a little boy. I was a Jap now. I had to rinse off." Once rinsed off, Sarno returned to the tub’s edge. "It was time to put that foot in the water," he said. "Awww! No way. That stuff was boiling. She started to laugh. She said, ‘You no Maline. You’re scared of water.’ I wasn’t scared of anything. So I put my foot in halfway up to my calf. Whew! I was gritting my teeth, and she was really laughing. ‘You Malines…hot water scare you.’ She called me phony and whatever the hell. So I decided I had to show her up. I stuck both of my legs in. I was just shivering. Shaking. Like I was being electrocuted. I said all I wanted to do was get the hell out of that thing and get some cold water on me. She laughed. She really ranked on me—in a nice way. Finally, I decided that I was going in. I sat down in the boiling water. When that water hit my scrotum, whew. I went straight up in the air like I was going through a loop. I came back down right up to my neck and then back up again like a cork. I couldn’t handle it, but she showed no mercy. She was laughing her ass off, sitting there cool, calm, and collected. I squirmed around and gritted it out. After a while I couldn’t even feel my body, but it was relaxing. A nice flush feeling came over me. We spent about ten minutes in there. It was humid in the room, but coming out of the water was like coming out into air conditioning. I didn’t even feel my skin. It was like velvet. We got our robes on, I put my arm around her waist, and we walked back to the room. I couldn’t even feel my skin, and she kept on laughing." Back in the room, Yoshiko asked Chris if he wanted a back rub. He had never had one in his life, so he said yes. "I took the robe off and I lay down on my side," Sarno said. "She got behind me and started to rub my back with her fingers. I felt like I had no skin on. It was a feeling like I was smooth all over, like a cat, and it was a great sensation. I almost went to sleep, but she woke me up and said, ‘No sleepy now. Later on tonight I give you best back rub of your life - wow!’" Sarno said that Yoshiko wanted him to buy some civilian clothes. With his thick black hair, a white shirt and navy blue trousers would give him a Japanese look. But Sarno nixed that idea. "I have to say in all honesty," Sarno reflected, "the Japs are racist people in their own right. To them, the Japs are the chosen people." However, Chris Sarno was an American Marine who was proud to wear his uniform. He had no intentions of trading it in to get the ‘Japanese look.’ For 15 or 20 cents, the hotel’s laundry service had already cleaned and pressed his uniform, and that’s what he wore for his first night of R&R in Kyoto. The couple went to the R&R Hotel. "We took the elevator up to the tenth floor," he recalled. "I can still picture today walking in and seeing the white tablecloths and all the Japanese girls lined up in their uniforms to wait on us. It was a typical restaurant atmosphere with Navy guys, Army guys, Marines, and guys in civvies—all R&R guys. Everybody behaved, and it was a nice feeling." Sarno ordered filet mignon and Japanese beer, but Yoshiko ordered nothing. Yoshiko didn’t like American food and she didn’t drink beer or alcohol, so she just watched her companion eat. "She told me that she was familiar with the R&R Hotel because she had been there with Army GI’s before," Sarno said. "But she said that I was the first Marine that she had gone on R&R with." There was teasing and banter between the two of them during the meal, and Yoshiko sipped orangeade while Sarno ate. When he was finished, they went out onto the streets of the city to find a Japanese meal for her. "There were Japs all over the street," Sarno recalled. It was not a street for automobiles. It was a narrow pedestrian mall. "The streets were no more than 20 feet wide," he said. "A car couldn’t come down those streets, but carts went up and down them as vendors sold whatever they could to make a buck. I looked all around me, figuring that I would get a knife in the ribs or whatever. She told me to relax and that I was safe. She said that after World War II, the Japanese people didn’t like the Marines at first because of the war, but when they found out that we treated the civilian populace with respect, their opinion of American Marines changed. Some Japanese bowed as they went by us. When I asked her why they did that since I didn’t know them, she said they were being polite. That’s when I started to realize how polite the Japanese people were." "We stopped in a little wooden place with a mamasan and papasan running it," he continued. "Everything was small in Japan. We sat down at a small table, and I sat in a space where maybe two and a half Japanese people would sit. I found Japanese accommodations to be very tight. Anyway, they had a big steamer and they put a bowl with noodles in it and a piece of cooked fish and a little vegetable. That’s what she wanted to eat. Now it was my turn to watch her eat with the chop sticks. I never mastered chop sticks. Never did. But she did. She brought the bowl of noodles up to just below her mouth and she got those chopsticks going. They were going like a machine gunner—loading, firing, reloading, breaking the jam down quick. She didn’t miss a beat, and she didn’t miss a noodle either. When she finished eating the ingredients, there was liquid left in the bottom of the bowl. When I asked her how she was going to get that out with chop sticks, she took some bread and dipped it in the soupy pot and absorbed all the soup." After she finished eating, Yoshiko and Chris went back to the R&R. They found a seat beside another uniformed Marine and his girl, and enjoyed what remained of the evening, dancing and partaking in the light-hearted atmosphere in the R&R Hotel. From there Chris and Yoshiko took a rickshaw ride back to the Oriental Hotel and took a quick shower together. "I wasn’t going to get in that tub again," Sarno said. On a Japanese-style bed (a futon mattress on the floor), they enjoyed a night of sex. "And you know," Sarno reflected, "to this day—I spent five nights with her—I can’t remember the sensation of sex with her for some reason. It was like being in Marine Valhalla to me. I was in a situation that I would probably never be in again in my life. I wanted to remember every detail. Instead, I can’t recall the sexual gratification with Yoshiko. Maybe because I wasn’t in love with her. I looked at her like a prostitute. She was doing this simply because there was money involved. I enjoyed it, but it wasn’t long, lingering love. It was just relief. Yeah. I have to be honest with myself. I remember her very clearly. Eventually I even fell in love with her. But at that stage, I wasn’t in love with her. I liked her and we had fun. I enjoyed the sex, but I can’t even recall it." He does recall his second day of R&R. He and Yoshiko went to a Japanese haberdashery to get Sarno some civilian clothes. "I watched her in action with the Jap salesman," he said. "She reminded me of my mother caring for her brood of kids. She was in control of the sales, and gave the salesman a run for my money. A white shirt, navy blue pants, two silk ties, and white underwear all came to $10.00. She saved me from getting ripped off." Chris and Yoshiko then went to a Cinemascope movie. It was a new technique, and one that the former American movie theater employee had never seen before. The Technicolor movie was by 20th Century Fox, and it starred Richard Widmark. It was the first of two Cinemascope movies that Sarno saw while he was in Japan. He liked the Widmark movie, but his second trip to the movies in Kyoto ended abruptly and unpleasantly. "It was a western movie about a cavalry officer taking care of a wagon train going through hostile Indian territory. Guy Madison was the star. The co-feature was a black and white kamikaze film—a Jap show," he recalled. "It was a big theater, with mostly Japs and very few G.I.s there," he said. Every time the kamikazes took off, the Japs would start crying. Not loud, but you knew that every time it showed them taking off, the audience was affected. Those guys weren’t coming back. Then it showed a B-29 being shot down. In the next scene, they were picking through the wreckage. All the Japs were cheering. I said to Yoshiko, ‘What’s the story? They’re cheering about killing a man.’ But she just said, ‘Hush, hush.’ You know - she didn’t want me to say anything. But I said, ‘Don’t say anything? What do you mean don’t say anything? Who won the war? America won the war.’ Yoshiko said, ‘Be quiet. Come on, don’t make a fuss.’ But I told her I wasn’t bothering anybody. When the Jap planes took off again in the movie, everybody cried, but I clapped. Clap - clap - clap - clap. Because they were going to get shot down. But she said, ‘Don’t do that. Japanese punchy-punchy.’ I told her that I would punchy, punchy the whole place out in return. She wanted to leave, but I wanted to stay." Reason got the better of Sarno, however. He realized that the room was packed with Japanese and they were all looking at him. If a fight broke out, the MPs would be called and his R&R would be short-lived. "But I was sort of laughing when we left the theater," Sarno said. "I told her that I didn’t understand the Japanese. I stick up for my side and it’s wrong. She sticks up for her side and she’s right." Sarno suddenly realized that American Marines were not the only prejudiced people in this world. The Japanese were prejudiced, too. In conversations with her, Chris discovered that Yoshiko’s family didn’t fare well during World War II. Born in Osaka, some 20 miles away from Kyoto, she lost a large part of her family in the 1940’s war. Her brother was killed by Marines at Iwo Jima. Her sister was killed in a bombing raid at Osaka, and so were her mother and father. "That’s how she ended up being a prostitute," Sarno explained. "She had a limited education, and without a family, there wasn’t much social acceptance. Family means everything in Japan. Yoshiko said that she could have gone to live with relatives when she lost her family during the war, but she knew that she would always be treated like a poor cousin because she wasn’t a part of the immediate family." She also couldn’t intermarry with an American on occupation duty in Japan. "A stranger coming in wouldn’t be accepted because he was not Japanese," she told Sarno. When he told her that was racist, she pointed out that the same thing would happen if she married an American and then went to live in the States. "The light went on," Sarno said. "I realized that a lot of guys would be calling her a gook or slant eye or whatever." At that point in time, both the Japanese girl and the American Marine realized that they were both prejudiced in their own way. But the respect that they had for each other gave them some middle ground. "We had talks about the USA versus Japan, as both of us were tempered by wartime youths with different approaches of who was right to go to war, Japan or the USA," he said. "We felt akin, yet it took time to mesh as one. We got along great together—her teaching me her ways and me with my ways. It was fun coming together." From the theater, the two people from different worlds took a walk to the beautiful Heian shrine. Along the way, they bought some ice cream. When the waitress brought the cool treat over to them, Sarno laughed at the small size of the scoop. He ordered five more scoops, telling Yoshiko to translate to the waitress that he needed a "taksan" not a "skoshi" order. "She came over to us giggling, and put the five scoops in front of me," he said. Those five scoops would make two scoops of American ice cream." Sarno treated some nearby Japanese children to ice cream, and in return he received bows of thanks from the youngsters. The more he saw of Japan, the more Chris Sarno came to appreciate the simple way of life, the Japanese people’s obedience to the law, and their cleanliness. "It was a nice, easy day," Sarno recalled. "I remember watching her eyes light up as she taught me her customs. She was a proud Japanese and without vulgarity. I loved her midnight black hair and modern Asian hairdo, her black eyes and oval-shaped face—so unlike the Korean and Chinese moony-shaped faces. I was slowly realizing that the Japanese were the elite of Asians, by far." Yoshiko wanted to take Chris to meet her sponsors—the people who now took care of her and provided a home for her. "Yoshiko came from the other side of the tracks," Sarno said. "She was working because they were poor. They lived in basically two houses." There were areas for sleeping and cooking, as well as a big wooden hot tub on one side where they bathed every night. "Every night, as poor as they were, they bathed," Sarno remembered. "The North Koreans and the Chinese gooks were dirty rotten bastards. But to the Japanese, cleanliness counted. They were the cleanest people I ever saw in the Orient." Sarno was reluctant to go with her to see her sponsors, because he didn’t want to share her and his time with her with others. But Yoshiko was persuasive. He said he agreed to go with her, but he complained all the way. The street to Yoshiko’s home was lined with weather-beaten wooden shanties. As Chris and Yoshiko walked down the dirt sidewalk, the side of one of the shanties collapsed in front of them. "All of the sudden," he recalled, "right in front of us, maybe ten feet before we got to it, the side of this guy’s house fell right out on what would be the sidewalk. His whole damn house partition was laying on the side and you could look right into his furnishings. His wife was running around all in a dither, and the little kids were clamoring. He came out on the sidewalk in baggy pants with a cloth belt tied around his waist. He was really poor. He was bowing down almost to his ankles to me as we approached him." Sarno offered to help him put the wood panel back up, but Yoshiko explained to him that the man was embarrassed and didn’t want him to help. "His family members came out and so did the neighbors," Sarno said. "They all put in a pitching hand, but he didn’t want me to touch the house because he was totally embarrassed. It wasn’t that I was a Marine; it was that they were so conscious of infringing on somebody—sort of like the reversal of how we would look at somebody in distress. You know, we’re going to pitch right in." After detouring around the fallen shanty, Yoshiko and Chris went on their way to Yoshiko’s home. Mamasan greeted them at the door. Two young boys around 10 and 12 years old were also at home. Chris was introduced to the family, and he took off his shoes to enter the main part of the home. Conversation was in Japanese, so Chris had time to look around at his Japanese surroundings. When the phone rang, Yoshiko answered it. After talking for a while, she handed the phone to Chris and told him to say "mushy mushy"—which was the Japanese equivalent to hello. His pronunciation of the words caused a lot of laughter in the household. In honor of Sarno’s visit to their home, Yoshiko’s "parents" prepared a meal. The children played a board game while the meal was cooked. At some point in time, Sarno had to use the bathroom. Even that simple task was an eye-opener for the American. "There was a bench-like thing that you sat on, and there were openings like a wooden seat," he recalled. "When you had to do a movement, the waste was collected in a drum split in half underneath. When I came out, I asked the boys how long the waste was kept there. They said it was picked up every three days by a guy that came around cleaning out the toilet. They called him the honey bucket man—that was the slang expression for it. When I asked them what they did with the waste, they said the honey bucket man took it to rural areas and sold it to the farmers for fertilizer in the rice fields." At Camp Fisher, Sarno and the other R&R Marines were warned not to eat the native food because it was grown with human waste fertilizer. Those not used to it generally got diarrhea from eating it. "Mamasan got a big black frying pan and put it on the hibachi," Sarno said. "Using thin, shredded vegetables with thin strips of meat (ox), she cooked something that looked like sukiyaki. The brown sauce and black mushrooms looked great, and it smelled good. She asked me if I wanted to eat and I told her no, but she kept cooking. To me, it looked like Chicago chow mien. Then when she was finished and started serving it, I told her that I wanted some. I hadn’t eaten yet, and I was hungry. I had never eaten with chopsticks before, so I was their entertainment for the night. The food tasted great, and I had a good share of it." But back at the hotel, Sarno discovered why he should have taken the Camp Fisher warning more seriously. "I got the trots," he said. "I just made it to the head. Now a Japanese hotel didn’t have a toilet. There was a receptacle in the bottom of the tile floor where you had to squat to do your duty. So I had the Japanese splatters and the next thing you know I was sitting in the damn thing. I said to myself, ‘I don’t believe this.’ Back I went into the shower." Yoshiko asked him if he was okay, and Sarno asked her the same thing. The Japanese girl was feeling just fine, and told her American companion that he just had a weak stomach. But Sarno knew it had nothing to do with a weak stomach and everything to do with being stupid. "I was told not to do it, and I did it," he admitted. While he couldn’t handle the Japanese meal prepared by Yoshiko’s mamasan, Sarno found a breakfast favorite at the Oriental Hotel. "In the Japanese hotel," he said, "there was no American food. The only thing they had was a ham sandwich. But I caught on to their deep-fried tempura. To me, it was like butterfly shrimp—flattened out and in a nice golden brown batter. It was really sweet and tasty. Fresh. You could taste the salt water because it was fresh from the sea. They were about the size of a half dollar, and I used to order a half a dozen for breakfast. It wasn’t as good as the fried clams back home, but I loved fried fish. I drank Burley’s Orangeade when I ate the tempura at the Oriental Hotel." Yoshiko drank orangeade as well, but her breakfast was wafer thin strips of seaweed. "She gave me some to taste," he recalled. "As soon as I got it near my nose and took a whiff of it, Holy Christ. I almost puked. The strong fish odor from that thing—oh my God. I said, ‘No, this isn’t for me.’ Yoshiko ate a boiled egg with it. She put the egg on a little lacquered saucer, broke the yolk, dipped the seaweed in it, and then chewed it. I thought to myself that she must have the stomach of a goat." Although Chris Sarno cannot remember all the 24/7 events and places that he saw while he was on R&R in Kyoto, he has memories of going to restaurants and cabarets. In one restaurant, he ordered southern fried chicken and tempura. The food was good, and Sarno was introduced to yet another new experience. "Beside the plate," he recalled, "were two white hand towels. There was a rolled up white cloth, and you could see the steam vapors coming up from it. It was hot—very hot and steamy like you find in a barber shop after the barber shaves you. Yoshiko told me that it was to clean my hands, fingers, fingernails, and face before I ate. It was a little hot and humid at night in Kyoto at this time, enough to make you a little uncomfortable. So it felt refreshing to have a nice cool skin and face and real clean fingers before you had a nice meal." He was more than disappointed with the food portions in the restaurant, however. "A half of their chicken was like a chicken leg with a little thing to it in the States," he said. "I asked for two more servings. I guess things were so stringent over there because the food supply was limited. Maybe they weren’t big eaters. I know they were big rice eaters, but I wasn’t going to eat that stuff. To me, that was gook chow. I wanted my American chow." One other evening, Yoshiko introduced her Marine escort to the owner of a Japanese cabaret. "It was a small, U-shaped alcove with a couple of stools and a little half bar," Sarno recalled. "It only held about 20 people. It was a lot different than going to a cocktail place in the United States. The Japs were small, so when I went in there I was like a bull in a tea shop. I needed some space due to my size." The cabaret owner would not allow Chris to pay for his beer or her orangeade. Chris and Yoshiko stayed there for about a half hour before they went on to the R&R Hotel ballroom. "She was so happy that I came and met her friend," Sarno said. "He bowed very deeply to me to come back." At the R&R, the young couple danced on the penthouse out in the open. "It was a nice, warm summer’s night," Sarno recalled. "You could look over the city from the penthouse railing and see the railroad station, all the lights, and the different flags on the banners of the city. It was nothing like the States. It was better than the States. Different customs. Different laws. You could do more with a woman there than you’d get arrested in the States for doing. Different social customs. And I liked that difference. " Generally, Yoshiko wore American-style clothing, but earlier that day, she had asked Chris to buy her a kimono. Although he liked her western look and considered kimonos to be sexless garments, he gave her $25.00 to buy it, along with another $5 to have lunch. "She went out happy as a bee," Sarno said. "I had a filet mignon and brandy alexander lunch at the R&R and went back to the room. In she came wearing the kimono. She looked altogether different. I will always remember that she didn’t say anything. She just stood there and looked at me. Black hair. Shiny. Smiling. She wore a white summer kimono with blue speckled little dots on it with a red obi around her waist. The kimono was up to her neck and right down to her toes. She didn’t look sexy. To me they didn’t project sex—just a kimono doll. But to her, I guess, it was a big deal for her to have it. She said that she wore American clothes, but she was still Japanese. That was okay with me. She looked beautiful. She was very beautiful. I’m glad I bought it for her, because she showed me that she was totally happy in having it. I felt good about myself that I had given it to her because I knew that she was happy. She was beaming. There is something about that moment that still grabs at my heart. I was too dense to realize that she was falling in love with her first Maline. Yoshiko was radiant dancing in that kimono, and having a relationship with her came natural, even though money was involved. We went back to the hotel, and I lost myself in her arms." While Sarno was the one with the money, Yoshiko was the one with the maturity and the worldly knowledge of intimacy between a man and a woman. "She taught me how to please her rather than please myself," Sarno recalled. "She taught me how to be a lover rather than just ‘wham bam, thank you ma’am, time’s up.’ Being close like that with Yoshiko was long-time love, not short-time love." That was the day before his R&R was over. It was also the day that Sarno ran out of money. He had turned all of his money over to Yoshiko soon after meeting her. "You see," he explained, "The Japanese woman controls the money in every household. When the husband comes home, he turns over the paycheck to the woman and she runs the household. I gave her about $125 because I cashed my other $75.00 into yen. Why I gave her my money I don’t know. For some reason, I trusted her, not even knowing the background of the Japanese woman controlling the money. But the fourth day was over and I was out of dough. We were living high on the hog before the money ran out. I asked her if she wanted me to leave now that I was out of money and still had one more day to go. But she said that she would pay for everything we did on the last day." What she made off of Sarno she was willing to spend so they could have another night and day together. "I treated her royally," he said. "I gave her everything—every last cent I had. If I had had any money left over at the end of the five days, I probably would have given her the remainder anyway, knowing how tough it was for her to make a living." That final day together, Sarno wanted to send a present home to the States to a girl who had written him letters while he was in Korea. "She lived about 50 miles from where I lived in Medford," he explained. "There was no romance. She was just a pen pal. We just traded letters. I wanted to send her a geisha doll that cost 25 bucks. Yoshiko showed another side to me now. She said, ‘You’ve got a girl home in the United States and a girl in Japan. Girl home is #1 ichi-ban and I’m #10?’ In Japan, #10 means you’re the worst. #1 means the best. I told her, ‘No, no. You’ve got it all wrong. You’re my #1 and you’re right here.’ But she called me Joe Butterfly. That was a term applied to G.I.s who went from one prostitute to another at their own discretion. I told her that I was no Joe Butterfly—she was the butterfly. She went from G.I. to G.I. She didn’t like me saying that and she got mad. I hurt her feelings. Then I apologized to her because I knew that the expression had saddened her." Sarno asked Yoshiko to pick out something for the girl back in the States. She picked out a Japanese garment, and it was mailed out to her. "She was jealous," Sarno said. "Jap girls are jealous. They figure that if you’re with them, they like you and you like them. That’s it. You aren’t supposed to look at another woman. But I was single. I was a Marine. And I was not in love with her. We had fun together, but I wasn’t looking at her in a serious way." Still, single Marine or not, Sarno did not like the fact that he had hurt her feelings. "I kept reassuring her that she was my #1 ichi-ban Japanese girl. She kissed me on the cheek and I kissed her on the lips and whispered in her ear that she was my #1. When she told me to ‘prove it’, I told her that I would—tonight." She started to laugh, and the tension in the air eased up. It was not easy for Yoshiko to understand that Chris Sarno’s true #1 mistress was not any woman—whether in Japan or the United States. "I had no Number One girl," Sarno said. "I was in the Marine Corps, I was single, and I would remain single while I was still in the Marine Corps. That way, I didn’t have to expend useless energy worrying about anything else but myself, completing my mission, saving my men, protecting my men under me, and following orders from my commanding officer. The Marine Corps was my mistress." But for just a little while longer, his duties in the Marine Corps were shelved as he enjoyed the final hours of his R&R. Early in their relationship, Yoshiko had asked Sarno to buy her a kimono. Now Sarno asked her to pick out a gift for him. "She picked out a scrapbook," he said. "It was a big one about 2 ½ feet long and almost 2 feet, four inches wide. I had pictures of Korea and Japan, so it was the perfect keepsake. The cover was a garnet-colored lacquer with a picture of the inland sea. It had the waves and jutting pine trees. It was a really nice gift and I still have it to this day. Every time I open that up, I think of her. It’s still in perfect condition. It is my bridge to R&R and to Yoshiko." In the final hours of his R&R, Yoshiko went with him in the taxi to Camp Fisher. "I hated to leave Yoshiko," he said. "Before we took the curve to the main gate, she asked me if I wanted to have a final short time [sexual intercourse] with her. Damn right I did, but where? She had a girlfriend who lived near Fisher Main Gate, so we spent a good hour together. Then we strolled to the main gate. About 100 yards from the Marine sentries, she bade me a nice farewell and said that if I came on R&R again to find her. I informed her that it takes six months for R&R to come back for me and I would be home in the USA in three months. When I got to the main gate and looked back, Yoshiko was waving to me with tears in her eyes. I waved back and entered as the sentries shook their heads. I silently said to myself, ‘screw you bastards. I had the time of my life. Now back to Shitsville.’ |

||||

|

||||

|

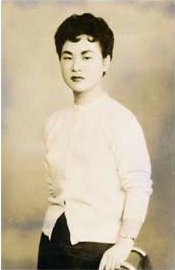

Yoshiko

was a little older than Chris, but not a lot. "I was 20 years old," he said, "and she must have been about 23 or

24. She had shiny, jet black Oriental hair and sort of slanty eyes. Unlike the Koreans, who had boney faces and

high Mongol cheeks, Yoshiko had the traditional Japanese almond-shaped face. She had a nice smile and a real nice

figure. She wasn’t dressed tacky. In those days, Japanese women wore skirts below the knee, similar to the way the

girls dressed back in the United States. In fact, the Japanese women, especially the young girls, couldn’t copy

enough of the American way of life. MacArthur’s occupational scheme of things was working. He was Americanizing

this country on an accelerated course. The women benefited more than the men, and the young people were picking up

on that real fast."

Yoshiko

was a little older than Chris, but not a lot. "I was 20 years old," he said, "and she must have been about 23 or

24. She had shiny, jet black Oriental hair and sort of slanty eyes. Unlike the Koreans, who had boney faces and

high Mongol cheeks, Yoshiko had the traditional Japanese almond-shaped face. She had a nice smile and a real nice

figure. She wasn’t dressed tacky. In those days, Japanese women wore skirts below the knee, similar to the way the

girls dressed back in the United States. In fact, the Japanese women, especially the young girls, couldn’t copy

enough of the American way of life. MacArthur’s occupational scheme of things was working. He was Americanizing

this country on an accelerated course. The women benefited more than the men, and the young people were picking up

on that real fast."