[KWE Note: We are currently seeking information about this Globemaster crash and

encourage anyone who had information or details about it to share it on this page of the KWE’s Airplane

Crash topics page. Contact Lynnita Brown,

lynnita@koreanwar-educator.org or phone 217-253-4620

(Illinois) in the evening; 217-253-5171 Thursday-Saturday 10

a.m. - 3 p.m..

Most recent addition: August 13,

2021

5

Page Contents

Back to Page Contents

About the Crash

A Douglas C-124A-DL Globemaster II aircraft (registration number

51-0141) departed from Kimpo

International Airport on February 22, 1957, and crashed shortly after takeoff at 20:00. There were 159

occupants on the plane (10 crew members and 149 passengers), and of those 22 were fatalities. The plane was

written off as a total loss.

According to the website www.planecrashinfo.com:

“The No. 3 engine seized, causing the propeller to come loose and slice through the side of the

fuselage making two full turns before exiting. It took two men out with it, idled the No. 4 engine and cut

the throttle cable. While attempting an emergency return landing at Kimpo Air Base, level flight could not

be maintained and the aircraft descended, crashing into the Han River.”

According to Antony J. Tambini's book, Douglas Jumbo's: The Globemaster (pp. 136-137):

"Departed Kimpo AB, Korea for Tachikawa AB, Japan. After take-off, and upon reaching climb power,

the number 3 engine started backfiring, subsequently explosions were heard, and the engine caught fire.

The engineer feathered the engine, and the pilot declared an emergency and started to return to base.

Parts of the exploding engine flew into the lower "P" compartment and struck hydraulic system components.

The pilot subsequently lost aileron control, and at the same time the engineer reported a loss of power on

number 4 engine. Maximum power was applied to number 1 and 2 engines, the pilot and co-pilot

maintained wings level with the use of full rudder trim. The aircraft crash landed into a river,

with the landing gear in the up position. The aircraft was destroyed. There were 3 fatal, 3

major, and 4 minor injuries."

According to the website aviation-safety.net:

"The Douglas Globemaster operated on a Military Air Transport Service (MATS) flight from Korea to

Japan. Flight MATS 503, departed Seoul-Kimpo (SEL) approx 18:00. Take off was made on runway 32. The

aircraft lost a blade off engine nr. 3 just after wheels were started up. The blade penetrated the

fuselage, cutting both aileron and rudder cables and killing four passengers. Before engine nr. 3 could be

feathered another blade separated from engine nr. 3, knocking out engine nr. 4. With full power on engine

nr. 1 and engine nr. 2 the aircraft wanted to roll over to starboard. Aircraft Cmdr Cartwright reduced

power on both running engines to prevent a wing-over. With no directional control at 100 feet AGL and the

DMZ just two miles ahead, a mud bar in the Han River was the only option to save crew and passengers, for

if they had crossed the DMZ, North Korea would have shot down aircraft.

The top passenger deck collapsed on impact, crushing some passengers and injuring others. Incoming tide

from the Han River Estuary reduced the mud bar. Survivors had to cling to ice flows in the river. The US

Army 1st Helicopter Amb Company evacuated 128 survivors to 121st Army Evacuation Hospital or to a levee on

the west side of Han River."

Back to Page Contents

History of Flight

"C-124A, number 51-141A of the 22nd Troop Carrier Squadron (heavy) APO 323, departed Tachikawa Air

Base, Japan, at 13171, 22 February 1957, to airlift 156 Army "Rest and Recreation" personnel to Kimpo Air

Base, Korea. En route to Kimpo the Aircraft Commander was flight checked on route procedures by an

Instructor Pilot. The flight was uneventful except for moderate turbulence which permitted only one

internal nacelle check which was accomplished approximately 3 1/2 hours after take-off. The aircraft

arrived at Kimpo at 18131.

At Kimpo the aircrew performed a thru-flight inspection. The only discrepancy noted was a loose

fuel trap drain line on the number 3 engine. The scanner repaired the drain line. The aircraft

was serviced to 24,000 pounds ramp fuel and 149 Army "Rest and Recuperation" personnel were on-loaded for

the return flight to Tachikawa. Take-off gross weight was 171,404 pounds with a center of gravity of

30.4 percent M.A.C. (within allowable limits). Weather at time of take-off was, "Clear 12 238/31/30

W5-022". Air Traffic Control clearance was, "Airways Green 3 to Nagoya, Green 4 to O'Shime, and Plus

14 to Waver; maintain 9,000 feet; climb unrestricted." The Instructor Pilot elected to fly the

aircraft on the return flight to administer training to a newly assigned pilot who was undergoing training

for co-pilot status.

The aircraft departed Kimpo on runway 32 and became airborne at 19531. The flight progressed

normally through reduction of power to climb power. Very shortly after establishing climb power and

at 900 to 1,000 feet of altitude, an engine backfire occurred. The scanner made a visual check and

reported the number 3 engine backfire. The pilot ordered the engineer to reduce power on the number

3 engine. The backfiring progressed to sounds described as "explosions". The engineer reported

a loss of torque on the number 3 engine and the scanner reported fire on the outboard side and white smoke

coming from the power section of the number 3 engine. The pilot ordered the engineer to feather the

engine and declared an emergency with intent to return to Kimpo for landing on runway 14.

The scanner continued his description of the malfunction as, "number 3 engine exploding and parts

flying off and striking the number 4 engine and the side of the fuselage." A hole appeared in the

side of the fuselage and the door to 'P' compartment raised and white smoke with the odor of hydraulic

fluid escaped. The door immediately fell back to the closed position and remained. The pilot

lost aileron control and the engineer reported a loss of power on the number 4 engine. The pilot

instructed the engineer to not feather the number 4 engine as long as it was developing power. He

then ordered the student co-pilot to leave the seat and the Aircraft Commander assumed the co-pilot

duties.

When the hole appeared in the side of the fuselage approximately twelve (12) passengers seated in that

vicinity left their seats and went aft. Several of these passengers had been injured by flying metal

from the hole torn in the fuselage. The loadmaster attempted to get them to return to their seats

and when they refused, he seated them in the vicinity of the cargo platform.

Following the loss of power on the number 4 engine, the pilot applied maximum power on the numbers 1

and 2 engines and, with the aid of the co-pilot, was able to maintain a wing level attitude with full

rudder trim and full rudder. The aircraft was losing altitude at the rate of approximately 300 feet

per minute, so attempt to return to K-14 was discontinued and the pilot committed himself to crash

landing. The pilot (Instructor Pilot) asked the co-pilot (Aircraft Commander) if he wanted to try it

wheels up or wheels down. The co-pilot answered, "Wheels Up". The co-pilot rang the alarm bell

three (3) times.

The loadmaster and scanner instructed the passengers that had left their seats to hold on to whatever

they could (all other seats in the aft section were occupied). The loadmaster held on to the upper

seat rail (top of seat backrest) and the scanner positioned himself behind, and held on to the lift raft

rack.

The pilot turned the aircraft approximately 20 degrees to the right for crash landing in a river.

At approximately 300 feet the cockpit and flight deck lighting failed. The pilot turned on the

landing light switches, but the landing lights also failed."

Back to Page Contents

Manifest

Crew:

- Boiter, Ansel Luther (Air Force Maj., aircraft commander, Honea Path, SC). Boiter received his

pilot rating on 23 July 1942 and his senior pilot rating on 1 November 1949. (See fatalities)

- Cantrell, Robert L., 26 (Air Force, SSgt., load master,

Greenville County, SC)

- Cartwright, James William (Air Force Capt., instructor pilot, 37 years old, Elkton, KY).

Cartwright received his pilot's rating on 27 June 1944 and received his senior pilot rating on 9 July

1954. Died 1/30/1997 and is buried in Glenwood Cemetery,

Todd County, KY.

- Forrest, Robert J. (Air Force SSgt., engineer, Kings

Mountain, NC)

- Hile, Allen P. (Air Force SSgt., radio operator, Harrisburg, PA) (He died May of 1957 at Ft. Sam

Houston's Hospital. He died from a blood transfusion. He got yellow jaundice. He had

third degree burns over the lower portion of his body. He was survived by wife Evelyn V. Hile and

four children: Allen Jr., Jennie, Sue and Cheryl; and his parents, Mr. and Mrs. Joseph C. Hile.)

- Hutton, Harold S., 25 (Air Force 1st Lt., co-pilot, Lakin,

KS)

- McKenzie, Stephen, 19 (Air Force A3C, load master, Riverton,

KS)

- North, Robert L. (Air Force Capt., pilot, North Hollywood, CA)

- Reilly, Charles P., 40, (Air Force A1C, radio operator,

Ozone Park, NY)

- White, Joe N. (AF M/Sgt., Schroon Lake, NY) (see fatalities)

Passengers (incomplete as of 3/10/2021) - There were 149 Army passengers.)

- Aguilar, Francisco (see fatalities)

- Arold, Eugene T. (see fatalities)

- Barstow, Bruce E. (see fatalities)

- Boudreau, Frederick L. (see fatalities)

- Bowcock, Stephen A. (see fatalities)

- Brown, Caldwell Jr. (see fatalities) (see obituaries)

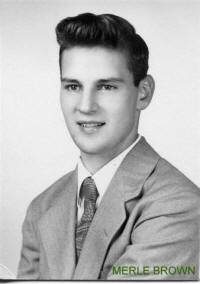

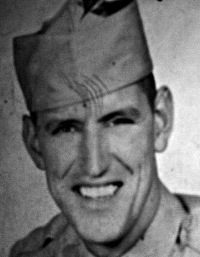

- Brown, Merle J. (see fatalities)

- Brown, SFC Vandy, age 22, Woodruff, SC (injured but

survived)

- Cain, PVT Harold L. (passenger - see Awards section)

- Carson, Franklin Delano, age 23, radio operator for 14

months in Korea (survivor)

- Clarke, PFC Warren J. (passenger - see Awards section)

- Clay, Jerry, 17 (Georgia) (passenger - received frostbite)

- Collaza-Gonzalez, Jose L. (see fatalities)

- Combs, Robert R. (Air Force 1st Lt., co-pilot)

- Crisman, SGT Forrest E. (passenger - see Awards section)

- Donaldson, Ben (passenger, home of record Indiana)

- Feil, Leon (survivor, now of Minnesota)

- Glass, Edwin Harold (see fatalities)

- Hills, George A. (see fatalities)

- Hocher, Donald L. (Army SP3, son of Mr. and Mrs. Carl Hocher, RR1, Collinsville, IL)

- Howard, PFC Alfred L. (passenger - Berkeley Springs - see Awards

section)

- James, PFC Elmus V. (passenger - see Awards section)

- Kawahara, Mark Hachiro (934th Support Btn - survivor) (died

February 23, 2018)

- Junkroski, Gerald E. (see fatalities)

- Levin, Lt. Bennett S. (Muscatine, IA)

- Meeker, Avery L. (see fatalities)

- Morris, Ernest Wayne (jumped into the river with another guy

on his back)

- Morrison, Ralph

- Myers, Ralph E. (see fatalities)

- Opiela, Andrew L. (see fatalities) (see Readers' Comments)

- Partin, Lewis P. (see fatalities)

- Phillips, Fred

- Scarborough, 1LT John R. (passenger - see Awards section)

- Silveri, Arnold (survivor)

- Speegle, Sgt. (survived - He was a medic from the 43rd

Surgical Hospital going on R&R.)

- Spencer, PFC Carey W. Spencer (passenger - see Awards

section)

- Stone, Jack G. (see fatalities)

- Wallis, Jan M. (see fatalities)

- Warner, Paul B. (see fatalities)

- Witherell, Harry E. (see fatalities)

Fatalities

- Aguilar, Sp2 Francisco (20 years old, Corpus Christi, TX-brother of Rudi Aguilar, Corpus Christi, TX)

(Supply, 63F, 24th ID)

- Arold, Sp3 Eugene T. (21 years old, Staten Island, NY)

Born 1935. Believed to be the son of Francis and Anna

Arold. Eugene is buried in St. Mary Cemetery, Richmond

County, NY.

- Barstow, Army 2d Lt. Bruce E. (29 years old, 240 Obispo Ave., Long Beach, CA, member of Det. R, US

Military Advisory Group, Korea - son of Mr. and Mrs. Eldred M. Barstow of Long Beach.

Born June 5, 1927, he is buried in Ft. Rosecrans National

Cemetery, San Diego, CA.)

- Boiter, Major Ansel L. (crew-aircraft commander) (Born April

29, 1920, he was the father of Suzanne April Boiter who later

married John Partridge Howland Jr., Jennifer I. Boiter, and

Ansel L. Boiter Jr. He was the husband of Mary Boiter who

later married R. Marvin Carter of Greenville, SC.) (Major

Boiter was a World War II and Korean War veteran.)

- Boudreau, 1LT Frederick L. (Philadelphia, PA - 25 year old son of Mr. and Mrs. Fred J. Boudreau of

Philadelphia)

- Bowcock, Pfc. Stephen A. (18 years old, Nelson, British Columbia)

(Born April 8, 1938. Member of HQ Co., 19th Infantry

Regiment, 24th Infantry Division. He is buried in San

Francisco National Cemetery, San Francisco, CA.)

- Brown, Caldwell Jr. (Bay City, TX) (see Obituaries - this

page) (24ID)

- Brown, Pfc. Merle J. (Army PFC, Blooming Prairie, MN - son of Justin and Grace Dawley Brown, born

September 22, 1936. Member of Company L, 19th Infantry Regiment, 24th Infantry Division. Buried in Rose

Creek Enterprise Cemetery, Mower County, MN.)

- Collaro-Gonzalez, Pfc. J.L. (San Juan, Puerto Rico)

- Glass, 2Lt. Edwin Harold (born 10/21/1932, 830 Cook St., Denver, CO - son of Charles and Molly Janet Ginsborg Glass, Denver, CO. Buried in Mt. Nebo Memorial Park, Arapahoe County, CO.)

- Hills, Pfc. George A. (29 years old, son of Mr. and Mrs.

Harold Hills, Raymond, NH) (C-52F, 24th Infantry Division)

- Junkroski, Gerald (Douglas, AZ - (born 15 June 1932; buried in Resurrection Catholic Cemetery, Cook

County, IL; parents Jacob & Agnes Junkroski; siblings Jacob "Jackie" - killed in North Africa in 1942

during World War II, Edward, Evelyn, Mary Ann, Elaine, Stanley, and Leonard.))

(HQ, 21st Infantry Regiment, 24th Infantry Division)

- Meeker, Sp3 Avery L. (age 20, Pryor, OK) (19th Infantry Regiment,

24th Infantry Division)

- Myers, Sgt. Ralph Edward (Lebanon, MO - husband of Mrs.

Betty J. Myers and son of Ralph Hatfield Myers. Born

September 22, 1933, he is buried in Springfield National

Cemetery, Springfield, MO.) (HQ, 21st Infantry Regiment, 24th

Infantry Division). See also: Newspaper Accounts, The

Beacon, March-April 1957.

- North, Capt. Robert L. (crew-pilot, North Hollywood, CA)

- Opiela, Capt. Andrew L. (buried in Holy Cross Cemetery, Cleveland, OH)

(see Readers' Comments - Michael Opiela.)

- Partin, SFC Lewis P. (Petersburg, VA) (Born 17 July 1920, Sergeant Partin served with the 21st

Infantry Regiment, 24th Infantry Division in Korea. His

widow was Arlasta Partin and his children were Ronald, age 11;

Johnnie, age 8; and Teresa, age 18 months. Sergeant Partin is buried in Wake Chapel Christian Church

Memorial Gardens, Middle Creek Township, Wake County, North Carolina.)

- Stone, 1Lt. Jack G. (24, Roseburg, Oregon, member of the

U.S. Military Advisory Group. He was the son of Mr. and

Mrs. Weldon W. Stone. His brother was Richard Stone.

He attended Roseburg schools and graduated from the University

of Oregon. He received an Army commission upon completing

ROTC training. He was called to active duty in May of 1955

and transferred overseas on October 10, 1956. He married Shirley

Brennen, daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Brennen on February 13, 1955.

They had one son, Bruce Alan Stone.)

- Wallis, Pfc. Jan Martin (20 years old, Sacramento, CA - son

of Dorothy Wallis. Brother of Ronald L. Wallis (USMC),

deceased.

Jan's mother, Dorothy Rothman Wallis Rodda, died September 21, 2012. Born

February 4, 1937, Jan is buried in San Francisco National

Cemetery, San Francisco, CA.) (HQ - 3rd Battalion, 19th

Regiment, 24th Infantry Division)

- Warner, 1LT Paul B. (Bellwood, PA - 28-year old son of Mr.

and Mrs. R.F. Warner and husband of Mrs. Carole Elaine Kellerman Warner,

who was the daughter of

Mr. and Mrs. J. Wilson Kellerman of Bellwood. Lieutenant

Warner was also the father of a young son named Scotty. Paul graduated

with a major in geography from Indiana State Teachers College in

January 1953.)

- White, AF MSgt. Joe Neal (crew member) (Schroon Lake, NY - husband of Mrs.

Jane E. Pitkin White, son of Mrs.

Emma Lee White, father of Deborah L. White Whitney who was born

August 8, 1948 in Merced, CA and died 7/31/2003 in White Plains,

NY. Born December 30, 1915, Joe is buried in

Alexandria National Cemetery, Virginia. He was a World War II

and

Korean War veteran. Joe's widow Jane died 11/01/1998.)

- Witherell, SFC Harry E. (East Lansing, MI) (Supply Co., 21st

Infantry Regiment, 24th Infantry Division) (Age 33, he was the

husband of Shirley F. Witherell of East Lansing. He was

also the father of sons James and John Witherell. Sergeant

Witherell is buried in Little Arlington, Evergreen Cemetery.)

Back to Page Contents

Survivors (incomplete as of 1/12/2017)

- Brown, Sfc. Vandy, Woodruff, SC

- Cain, Pvt. Harold L. (passenger)

- Cantrell, S/Sgt. Robert L. (crew) (received the Air Medal)

- Cartwright, Capt. James (crew) (received Distinguished Flying Cross)

- Clarke, Pfc. Warren J. (passenger)

- Crisman, Forrest E.

- Donaldson, Ben (passenger)

- Feil, Leon (passenger)

- Forrest, S/Sgt. Robert J. (crew) (received the Air Medal)

- Hile, S/Sgt. Allen P. (crew)

- Hocher, Donald L., Collinsville, IL

- Howard, Pfc. Alfred L. (passenger)

- Hutton, 1Lt. Harold S. (crew)

- James, Pfc. Elmus V. (passenger)

- Kawahara, Mark

- Levin, Bennett S. (see Eye Witness Testimonies)

- McKenzie, A/3c. Stephen A. (crew)

- Moon, Capt.

- Morris, Ernest Wayne

- Morrison, Ralph

- Phillips, Fred

- Reilly, A/1c. Charles P. (crew)

- Scarborough, 1Lt. John R. (passenger)

- Silveri, Arnold, Staten Island, NY

- Speegle, Sgt.

- Spencer, Pfc. Carey W. (passenger)

Back to Page Contents

Pilot/Co-pilot Information

- Total flying hours (including AF time, student time, and other accredited time)

- North (pilot) - 2384:25

- Hutton (co-pilot) - 437:00

- Cartwright (instr. pilot) - 7352:00

- Boiter (aircraft cmdr.) - 5733:00

- Total rated 1st pilot and instructor pilot hours, all aircraft

- North - 1853:25

- Hutton - 29:00

- Cartwright - 6626:00

- Boiter - 4120:00

- Total weather instrument hours

- North - 34:05

- Hutton - 23:00

- Cartwright - 1268:00

- Boiter - 429:00

- Total 1st pilot and instructor pilot hours this model (F-86, B-50, C-119, etc.)

- North - 33:45

- Hutton - 20:00

- Cartwright - 2846:00

- Boiter - 410:00

- Total other (command, a/c cmdr, co-pilot, radar control pilot) hours this model

- North - 34:25

- Hutton - 38:00

- Cartwright - 2987:00

- Boiter - 615:00

- Total 1st pilot and instructor pilot hours this model and series (F-84F, F-86D, etc.)

- North - 33:45

- Hutton - 20:00

- Cartwright - 805:00

- Boiter - 239:15

- Total other (command, a/c cmdr, co-pilot, radar control plt) hrs this model and series

- North - 34:25

- Hutton - 38:00

- Cartwright - 42:00

- Boiter - 292:20

- Total pilot hours last 90 days

- North - 61:30

- Hutton - 158:00

- Cartwright - 268:00

- Boiter - 66:00

- Total 1st pilot and instructor pilot hours last 90 days

- North - 31:50

- Hutton - 26:00

- Cartwright - 260:00

- Boiter - 66:00

- Total pilot hours (night) last 90 days

- North - 15:05

- Hutton - 55:00

- Cartwright - 94:00

- Boiter - 9:00

- Total pilot hours, weather and hood, last 90 days

- North - 10:25

- Hutton - 35:00

- Cartwright - 76:00

- Boiter - 15:50

- Date and duration of last previous flight this model

- North - 18 February 1957 - 6:00

- Hutton - 19 February 1957 - 8:15

- Cartwright - 21 February 1957 - 4:00

- Boiter - 16 February 1954 - 9:05

- Date and duration of last previous flight this model and series

- North - 18 February 1957 - 6:00

- Hutton - 19 February 1957 - 8:15

- Cartwright - 21 February 1957 - 4:00

- Boiter - 21 February 1951 - 9:05

Back to Page Contents

Eye-Witness Testimonies

Rev. Ronald C. Bauer (sent to the Korean War Educator):

"I came from St. Louis, Missouri originally, enlisting in the Army in January 1955, Fort Leonard Wood,

Missouri basic training, Ft. Lee, Virginia baking school honor graduate, Fort Sill, Oklahoma, Korea, then

Fort Hood, Texas. Following my discharge I attended the University of Missouri, Columbia, Missouri,

then finished college at the University of Oklahoma in Norman. I then attended Nashotah House,

Nashotah, Wisconsin, a seminary of the Episcopal Church. I briefly considered returning to the

military life, but my wife of the time would not agree to that move. I led churches in Oklahoma,

Kansas, Missouri, Minnesota, ending up retiring from St. Margaret of Scotland Church and School, San Juan

Capistrano, California, in 1998. In all I would have to say that the military and my experiences

there helped shape my character, maturity, and goals in life. It gave me a taste of moving I

probably would not choose by myself, making new friends and being responsible. I loved the

regularity of military life and the camaraderie."

--

"As best I can remember, it was a bitingly cold and colorless day in the winter of 1957-1958. My

memory is fuzzy on the exact month, however, I was walking towards the 121 Evacuation Hospital in ASCOM

City Korea early afternoon. An alarm began sounding and eventually helicopters began coming in, one

after the other, much like bees to a hive. At the emergency room I met Father Berry, the Roman

Catholic Chaplain, and his assistant, Owen (I cannot remember his last name). They told me that

there had been a C-124 Globemaster that had crashed in the Han River after taking off from Kimpo Air Base.

Chaos was evident everywhere, but, within the chaos, there was a determination and fervent

professionalism by all the medical personnel. Since we were between our resident Protestant

Chaplain, Father Berry asked me to see if I could get the regional chaplain. I did and his driver

drove him over in about 45 minutes. He seemed to be a bit unwell so I suggested he stay in the

chapel and pray. I then assisted Father Berry and his assistant Owen to discover the denominations

of the soldiers coming in on stretchers. All the injured were trembling violently from hyperthermia

and it took over an hour before most could settle down. I am sure that the terror of the plane crash

also contributed to their trembling. The crash obviously over taxed our facilities, but you would

hardly have known it. Everyone just dug in and worked at a frantic pace through the night until

about noon the next day, before things progressed from chaos to simply very busy. The emergency room

became a triage production line while the operating rooms and intensive care unit worked nonstop

attempting to operate on or stabilize the most severally injured. After several days, the most

severe injured, who needed further specialized care, were picked up and flown to hospitals in Japan.

The less severely injured continued their recuperation at our hospital. I'm unclear whether or not

they eventually continued on to Japan or returned to their units.

During the ensuing days my job was to help those who wished to write letters back home but needed help

doing so. I talked with those who needed to talk and prayed with those who desired prayer.

During this ordeal Father Berry incessantly kept telling me that I should become a priest. I

eventually did but in the Episcopal Church. In fact, this event was pivotal in prompting me to join

the Anglican Church in Korea and I took instructions under Father Matthew Imre, 8th Army Chaplain, and was

confirmed by Bishop Chadwell, the assistant Bishop in Korea. I also got to know Bishop John Daily,

who was the Lord Bishop of Korea, on a personal level that lasted for many years even after he retired

back to England.

We can all be proud for the actions of the medical personnel at the 121st Evacuation Hospital.

From the high ranking medical officers to the lowest medical aide, all worked together like a finely made

Swiss watch. Watching MASH years later brought me constantly back to my memories of this fateful

winter day in Korea, except we were not as crazy.

It was within a week that Father Berry, Owen and I drove out to the wreckage site and took pictures.

It was a mangled mess of a half submerged plane covered with snow and ice. A very bleak sight.

It is a wonder anyone survived. Those that did owed the pilot many thanks for their skill in

bringing the plane down as gently as they did. As terrifying as the event was, there was also

something majestic and noble about everyone who just did what they do best, heal the injured and in some

cases give the dying comfort, prayer and last rites.

Bravery comes in many forms and not simply on the battlefield. The pilots of the Globemaster, the

helicopter pilots, the doctors, nurses, hospital aides and the surviving soldiers all showed a bravery

that is a merit to the military service to which they belonged.

I was in Korea because I had volunteered for a friend. I began with the 130th Quartermaster

Bakery and gravitated to the next compound when the Chaplain's Assistant job became open. The plane

crash and the ensuing days was a seminal experience in my road to the Episcopal Priest Hood. You

could see the need of experienced medical personnel in such hectic situations, but you could also see the

need for spiritual comfort and presence. It was like an anchor for those with faith, and even those

who had no faith were often very accepting of our presence and ministrations. The character of the

chaplains and the medical personnel was just humbling."

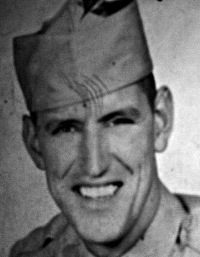

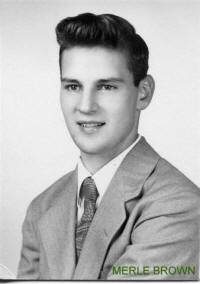

Fred Phillips

|

Fred Phillips 1957

(Click picture for a larger view)

|

"I was on the Globemaster that crashed in Korea in February 1957. One of my friends was a fatality.

His name was Gerald Junkroski, and he was from the Chicago area, I think. I just received some bad

bruises and the next day we were placed on another flight. I do not believe there was a manifest since we

were going on R&R. When we were boarding it was first come first served. I had missed two

flights. It was very horrible. I still dream about it. The pilots were outstanding in keeping

the craft level, however, it was destroyed.

The weather was very cold. Some places in the Han River were frozen over. As I mentioned, I had

missed two previous flights. For R&R, it was first come first served. That is probably the

reason there was not a manifest. When your outfit sent you on R&R, there was not an exact time to

return. For example, on one R&R I returned by ship to Inchon and had to hitch a ride back to the DMZ

where I was stationed. I was gone for 20 days. Since I did not have any serious injuries as a result of

the plane crash, I was issued more clothing at Ascom City and continued on to Japan. When I found your

posting, this was the first time that I had been able to obtain any info on the crash. I was seated on the

upper deck and that is probably the reason I did not receive any serious injuries. If the helicopters had

not arrived, we most likely would have frozen. I am going to look through some old things to see if I can

find any other information and will let you know.

Gerald Junkroski and I both were assigned to the 21st Infantry Regiment of the 24th Infantry Division.

We were both assigned to the communications platoon of Headquarters Company of the 21st Regiment. We

were assigned to the same Quonset hut and both held the rank of Private First Class (PFC). I think

he had been drafted. I had volunteered.

Gerald Junkroski 1957

(Click picture for a larger view) |

Gerald Junkroski 1957

(Click picture for a larger view) |

(Click picture for a larger view) |

He always kept an 8x10 photo of his wife close by, and talked daily of longing to be with her. He was a

very good man and friend. As I mentioned, I continued on to Japan for seven days and had initially thought

that Gerald had been injured. It was not until I returned to my unit in Korea that I found out that he had

been Killed.

I live in Jonesborough, Tennessee, and have retired after a 42-year law enforcement career."

|

Bennet S. Levin

(Click picture for a larger view)

|

Bennet S. Levin (sent to the Korean War Educator by Ben Levin, California)

(Click picture for a larger view) |

(Click picture for a larger view) |

(Click picture for a larger view) |

Silveri, Arnold (crash survivor)

[KWE Note: The following excerpt was taken from Arnold Silveri's new book, Turning the Corner on Life.

It was copied with Mr. Silveri's permission. Order information for his book can be found in the

General Store (non-fiction books) of the KWE.]

"It was around 7:15 p.m. when we headed for the plane awaiting us. It's one thing to read about

the specifications of a C-124, but another thing to see one up close. The Globemaster is a

tremendously big airplane. The front clamshell loading doors are located in the nose, under the

cockpit, with hydraulic ramps that angled down at seventeen degrees. When carrying heavy equipment,

the second floor (upper deck) folded up against both sides of the plane. with the upper deck folded

down, it added a second floor, creating additional seats of metal and webbing that folded down from the

sides of the plane. The C-124s were affectionately called Old Shaky by the flight crews who manned

them. The big engines caused vibrations, shaking, rattling, and squeaking during the fight.

The "Shakemaster" was another nickname among others for the giant double-decker airplanes...."

"... As you might expect, we were all happy and excited, as the four engines revved up loudly before

taking off. After all, we were going on R&R to Japan, not on our way to an airborne drop behind

enemy lines. The engines roared loudly as we headed down the runway and took off.

Now that we were in the air, we were relieved of any anxiety we may have experienced prior to takeoff.

About five minutes into the flight, though, our happy mood and chatter was suddenly interrupted by a loud

'explosive noise.' The force of the explosion shook and rocked the plane. It was as though

someone had thrown a hand grenade or explosive into a steel garbage can and covered it up. When I

looked across to the other side of the plane, I couldn't believe my eyes, there was a big hole in the

side. The explosion made a hole big enough to blow out the two men who had been seated there.

Several men, who had been seated directly across from where the explosion occurred, stumbled by us while

trying to make their way to the rear of the plane. They were cut up, bleeding, and obviously

traumatized by what had taken place. I think the swiftness of the events that had taken place caused

everybody to be stunned into a fearful, traumatic silence.

However, a few seconds later, the soldier sitting on my left began to wail. It was a long,

drawn-out cry of grief and emotion. The way somebody would wail at a funeral. I didn't know

for sure, but I don't think he was screaming out of fear or pain from an injury. It was as though he

had suddenly realized what had occurred and perhaps foresaw his own impending doom. A few days

later, I would sadly be reminded of him when I saw his name on the casualty list. It appeared in one

of the articles in the Stars and Stripes.

In addition to the hole in the right side of the plane, the bucking and shaking only added to the

realization of the emergency at hand. In those few seconds, my life flashed through my mind.

"How is my mother going to take this news?" I asked myself as I engaged in a self-confession of things I

had done wrong in my life. I can't speak for anyone else, but I think everyone on that airplane had

an awful lot in common with the soldier sitting on my left.

As the pilot struggled for control of the airplane, I remember seeing an amber light flashing. I

found out later, of course, what had really happened to cause the explosion and subsequent crash from an

article that appeared in the Stars and Stripes. Captain James Cartwright, the pilot, said,

'We lost power on the number 3 engine early on. It caught fire and started throwing chunks of

metal (engine parts) through the fuselage. The parts hit the carburetor or throttle linkage on the

number 4 engine, and it started to lose power.'

Captain Cartwright continued,

'Pieces of metal were coming through the fuselage, cutting holes big enough for a man to walk

through. The metal cut the aileron cables. It all happened in about five minutes, but it was

obvious we couldn't turn around.'

The pilot concluded by saying, 'A light fire was burning in the number 3 engine, and I rang the alarm

bell and radioed in the situation.'

Even though I knew we were in big trouble and were going to crash soon, I had no way of knowing when it

would happen. One account of the crash came from a sergeant, who said that when the plane hit, he

felt like he was being rolled down a big tunnel end over end. Another survivor, amongst several

others, interviewed by the United Press said, 'The plane fell just like the whole world coming to

an end.'

For whatever reason, I just can't recall or remember the feeling--on impact--when the plane actually

crashed. I've replayed this DVR--over and over in my mind--but the crash part of it has been erased.

Another guy said, 'There was a loud crashing noise, a big jolt that caused the upper deck to break and

collapse on those seated below.' The upper deck that had collapsed was amidst the smoke and twisted

wreckage. The impact put a hole in the bottom of the plane near the tail. A part of the right

wing was damaged.

Eyewitnesses said the plane was on fire before it crashed. An air force spokesman said the plane

burst into flames when it crashed.

In our attempt to escape, everybody ran toward the rear because the front of the plane was burning.

In the rush to get out, I was knocked down by someone from behind. Someone screamed. 'You

can't get out back there up here..." I got up and headed in the direction of the guy who was

yelling. When the upper deck collapsed on impact, it formed an angle that served as an exit ramp

(like an escalator). I made my way up the makeshift ramp that led me to an open door. When I

looked out the door, in the dark of night, I saw what looked like snow and ice on the ground below.

It was a pretty high jump, but this was no time to procrastinate. I was not about to linger there

and wait for the whole plane to blow up in flames. The fear of having the plane blow up while being

trapped inside had clearly motivated everyone to get the hell out of there--ASAP. I didn't realize

it then, but the plane was filled with fuel. First of all, the pilot had no time to even think about

dumping the fuel.

Moreover, according to a former air force mechanic, even if the pilot wanted to dump the fuel, there

was no method devised to dump the fuel from the C-124. Almost all of us were lucky enough to survive

the initial explosion causing the hole in the side, the damage to the engines, and other damages.

Most of us were also lucky enough to survive the actual crash or any other possible explosion that might

cause the whole thing to blow up. But how many of us would be lucky enough to survive the last but

most chilling part of this whole ordeal.

So without further hesitation, I reared back and jumped. I expected to land in the snow and ice

below the plane. Instead, however, I had submerged into the icy waters of the Han River. When

I emerged from the river, the water on me immediately froze, from my head to my toes. I could hear

faint cries and moans but was unable to see anyone in the dark or even determine where the sounds were

coming from.

The dim light emitted from the rear portion of the burning, smoldering plane enabled me to see a group

of men huddled in shallow water a reasonably safe distance from the back of the plane. I swam a

short distance, then pushed my way through the floating ice and water I made my way toward the

group, who were double-timing in place to try to keep from freezing. A couple of older sergeants,

who were holding flashlights, had organized us into a group, took a head count, and told us to stay right

where we were. "The shoreline is deceiving. It's farther away than it appears to be," said one

of the sergeants.

It was revealed later that the river was a mile wide where the plane hit. You have to give those

old-time sergeants credit for taking charge. We continued double-timing in place in the shallow part

of the river. We were on a sandbar (near the DMZ) on the northwest bank of the Han River. The

estuary (or inlet) of the Han River meets the Imjin River. Parts of the Imjin and Han lie over the

Thirty-eighth Parallel. I didn't know it then but found out later why the water kept rising as the

night wore on. The Yellow Sea flows into the estuary of the Han River. More importantly,

though, the Yellow Sea has an incoming nineteen-foot tide (the second highest in the world). Two of

the guys, suffering from burns and other injuries, were lying on inflatable rubber rafts. When they

asked for field jackets to cover up the two guys, I laid mine over one of the injured guys.

After spotting the flares shot off by one of the sergeants and the searchlights being poked in the sky,

the first helicopters arrived in about forty-five minutes. But some some unknown reason, they

disappeared for a short time. They reappeared, of course, and began evacuating the most seriously

injured (two men on the raft) first. With an air force plane circling overhead to coordinate the

helicopter operations by radio, the choppers skimmed the swirling waters to get the casualties aboard.

Captain Joseph Reindhart, commander of an H-19 helicopter of the Thirteenth Transportation Company, said,

"The river was chock full of ice." The Han River, known as the Highway of Ice, was probably closed

to all boat traffic. Captain Reindhart also said, "Every landing was a completely new experience."

For a period of ti8me, they were transporting the evacuees directly to the 121st Evacuation Hospital in

Inchon. However, the round-trip from the now rapidly disappearing sandbar to Inchon took forty-five

minutes. When they realized they were fighting time and the nineteen-foot-high rising tide, they

began dropping them off on the nearby riverbank. The medics then transported the evacuees by

ambulance to the 121st Evacuation Hospital. The caption in one Stars and Stripes article said

it best: "Tiny Copters Battled Time, Tide in Evacuation at C-124 Han Site."

By 10:30 p.m., the choppers had to hover in the air while the survivors scrambled up rope ladders to

safety. I didn't feel any immediate pain when I jumped from the plane into the water. However,

I can't determine whether it was the impact of the crash, or the jump into the river. But in any

event, the back pain started at the beginning of the double-timing. Between the decreasing nighttime

temperature, the rising icy water, and the increasing back pain, it was becoming increasingly difficult

for me to double-time. It got worse as the night wore on.

At some point, perhaps during the last hour or so, I was literally unable to continue to move around.

It was like a vicious circle. The increase of my back pain prevented me from double-timing which

caused me to lose body heat even faster. By becoming increasingly colder, faster, and my back pain

increasing in severity, it prevented me from functioning.

Obviously, by now, I was numb and totally helpless. There were very few guys left in the water to

be rescued after nearly four hours. When one of the air rescue personnel shined his flashlight in my

face, I don't know if my face had any color left to it. Whatever the color of my face was, he

clearly recognized the appearance and symptoms of hypothermia. One of them said, "We have to get him

out of here, now." I had been out there too long. They tied a tag on my shirt button and

walked me to the helicopter hovering above the water. While I was struggling to climb up the rope

ladder, somebody from behind shoved me into the helicopter. Thus ended the four coldest--and most

traumatic--hours I have ever experienced in my life. By twelve thirty, the crash site had been

abandoned by all. Except for a small portion of the airplane's tail, the nineteen-foot-high tide had

engulfed the plane.

In addition to the helicopter pilot and radio operator, there were two other evacuees in the

helicopter. The pilot went straight up, leaving my stomach on the ground, before turning and heading

on a downward angle toward the shoreline. The medics of the Forty-ninth, Fiftieth, and Fifty-fourth

Detachments and the Thirty-ninth Air Rescue Squadron did a great job of rescuing and evacuating us under

very difficult conditions. At times, the rising tide flowed over the floorboards of the helicopters,

increasing the danger of the operations. The awaiting medics gave us blankets and helped us get into

the truck.

When we arrived at the 121st Evacuation Hospital, we took off our ice-caked uniforms. One medic

slowly removed my boots and cut my socks off. We were given hot tea and hospital pajamas and a

blanket. When the medic saw how white and pale my feet were, he clearly knew just how cold they

were, even before touching them. With that in mind, the medic asked, "Do you have any feeling in

your feet?" "No, they feel numb and heavy, like bricks," I answered. I know that sounds

contradictory, like some kind of oxymoron. After all, how could my feet have no feeling, yet feel

numb and heavy like bricks at the same time. In any event, the medic began massaging my feet.

In between, he'd pinch me and ask me if I felt it. When I answered no, he continued his massaging.

After quite some time my circulation and body heat were slowly beginning to return. Finally, when he

pinched me again, I felt it, but just barely. I experienced a slight burning sensation and pain.

Yet according to current methods of treatment at the Mayo Clinic, the person's head should also be

covered. Warm compresses should be applied to the neck, chest wall, and groin, but not the arms and

legs. Warm fluids could be administered intravenously. Furthermore, there should be no massage

of any kind administered in such cases because it could cause further damage. But that was then, in

1957--fifty-five years ago--and this is now, in 2012.

Surprisingly, the 121 Evacuation Hospital was not equipped with enough beds and prepared for such a

large influx of patients. but the hospital's function was not so much as to house a large amount of

patients on a continuing basis. So they broke out the cots for us to sleep on that night. It

was, after all, an evacuation hospital. If you didn't require any hospitalization, you were quickly

discharged. If you were injured or sick enough, they hospitalized you. If you were seriously

injured or too ill, they transferred you to the Tokyo Army Hospital in Japan. While two of Captain

Cartwright's crew remained in the Kimpo Air Base Dispensary, Captain Cartwright and four of his injured

flight crew, of the 374th Troop Carrier Wing, were transferred to Tachikawa AFB Hospital in Japan.

In a later interview, Captain James Cartwright said, "The first impact wasn't so bad, but the second

was a lulu. The next thing I knew I was in the water outside the plane. I crawled on an ice

floe, and I like to froze. That's the coldest place I ever was."

We provided the hospital personnel with our name, rank, serial number, lunit, mother's name and

address, etc. Later, I was questioned by a medical officer about any pain, injuries.... I told

him my back felt a little sore. But I didn't make a big deal about it. They never took any

x-rays of my spine or offered any psychological counseling. The admitting diagnosis, I found out

years later, was (8740) exhaustion from overexposure to cold.

In retrospect, I suppose they could have kept me for another day or so. But that's the army for

you. It reminded me of the old army song: "You're in the army now, you're not behind the plow,

you're digging a ditch, ya son of a bitch, you're in the army now." Just so there is no

misunderstanding, the great Irving Berlin, who wrote this song and so many other great songs, did not

include our fourth line: "ya son of a bitch" in his great song. In the interim, we were visited by

Lieutenant General Palmer, the AFFEC deputy commander in Korea. He came around and asked us how we

were doing and if we needed anything. Two hundred men had volunteered to give blood when they heard

about the crash.

The next morning, many of us were discharged and would be heading back to our units. By Monday,

three days later, thirty men remained hospitalized (two in serious condition). Later that morning,

we were escorted to an empty Quonset hut to examine articles that were salvaged from the wreckage.

While sifting through the clothes and other personal items, I spotted my name tag on one of the field

jackets in the pile. The only reason I would have wanted to reclaim the jacket was because it was

fitted. I was horrified, however, when I opened the field jacket. The whole inside of the

jacket was stained with blood. I felt terrible and threw it back into the pile, in disgust. I

had no way of knowing, though, whether the person I had covered with my jacket was one of the twenty-two

men missing or killed. In order to aid in an upcoming investigation, we had to fill out a long

questionnaire about the flight and events leading up to the subsequent crash. After completing the

questionnaire, I headed back to the group. We were awaiting further orders to return to our

units...."

Sgt. Speegle (as told to Andrew N. Nelson)

[KWE Note: The following article is entitled, "The Han River

Crash". It was found on pages 12, 13 and 22 of Volume 105, No.

50, The Youth's Instructor, December 10, 1957, and is

reprinted on the Korean War Educator with the written permission of

the General Conference of the Seventhday Adventists, Silver Spring,

Maryland. The first name of Sgt. Speegle has not yet been

determined because it was located on the center fold in the magazine

and thus hidden from view in a PDF.]

"R and R. Rest and Recuperation. These magic

words mean a lot to GI's in Korea, especially in bleak winter.

So it was with a great sense of satisfaction and relaxation that

I got away from my work at the forty-third Surgical Hospital and

settled down in the huge Globemaster for a quick flight to

sunnier scenes in Japan.

The two hundred-passenger mammoth of the sky lanes had just

disgorged a load of returning GI's at Kimpo Air Base and gassed

up, and we had scrambled on and filled almost every available

space on both decks. Our plane was a C-124 troop carrier

from Tachikawa, Japan, which had been shuttling back and forth

carrying thousands of GI's without incident.

I found a seat near the front of the seventy-three-foot cabin

on the left side. I was just one man in a long row.

Along the opposite side was another long row and between these,

down the center of the plane, were two more, with men sitting

back to back. On the deck above were four more rows of

GI's--146 of us in all, besides the crew of 10.

We were soon taxiing out to the runway. After taking

aim, the sixty-ton giant stirred, began moving, gathered

momentum, and shot down the concrete strip to leap into the air

and head for Japan, just three hours and twenty minutes away.

Though a medic, I naturally felt no need of carrying

first-aid equipment on such a shot hop. Furthermore, the

plane carried a good supply if it were ever needed.

But that short hop was shorter than anyone had anticipated.

It was over in approximately four minutes.

At 7:50 p.m., Japan time, we were lifted off the runway into

a cold moonless and starless February night. Trouble

struck immediately. The propeller of the new inner

starboard motor spun off and fantastically made a complete

circle of the plane to crash into the pilot's compartment,

killing the flight engineer. The resulting terrific

revving up of that uncontrolled engine caused it to explode,

sending bullet-like pieces flying in all directions.

Just across from me there was a deafening crash. A

six-foot hole was torn in the wall of the plane by a flying

cylinder head. Two men, safety belts and all, were sucked

out into the night to plummet parachuteless to the dark ground

three hundred feet below! Any of us might have been those

two men had we chosen to sit there. Near-panic followed as

more flying engine parts tore into the fuselage, breaking pipes

and shooting hydraulic fluid all over the cabin. Men near

that gaping hole quickly unbuckled their belts and dashed

pell-mell toward the rear of the plane.

Fire broke out at once in the damaged wing. Then the

outer engine was struck by flying parts from the first engine.

It gasped and stopped. This left an impossible situation:

a huge Globemaster flying on only two engines, both being on the

same side.

We were not far from the rugged 38th parallel, and the pilot,

Capt. James A. Cartwright, faced a very rough terrain as he

skillfully struggled to bring his human cargo down in a darkness

illuminated only by our landing lights and the trailing torch of

the burning engine. A high mountain was dangerously near

and the treacherous, frozen Han River lay below.

We were now rapidly losing altitude, but we thought we were

returning to Kimpo until over the P.A. system we heard a call

for help. Then came the announcement that we were

ditching. We were told we would hit the river at the last

of six buzzes. I quickly pulled the hood of my light parka

over my head and offered a quick prayer as I faced away from the

momentarily expected impact.

Buzz one. Buzz two. Buzz three. Then came

the crash. The other three buzzes never sounded.

With the first impact, two of the second-floor sections at

the rear fell, pinning down many of the beltless men who had

fled there when the cylinder head crashed through the fusilage.

Above me some men were dangling on their belts, the floor having

fallen out from under them.

The second jolt was terrific, mercilessly throwing around the

rest of the unbelted men and giving all of us a bone-jarring and

teeth-rattling shake-up. This was followed by a short

slide and a sudden stop. Captain Cartwright had succeeded

in finding a comparatively soft spot to land.

There was a mad, fighting scramble to get out of the burning

plane. The danger of an explosion that would engulf jus in

flame was imminent. Nearly all of the eleven exits were

jammed by broken plane parts, baggage, life rafts, etcetera, so

all the men started climbing toward the roof exit.

I was impressed to remain behind alone. But I soon

realized that, with the plane on fire, I too had to get out.

Just then, I was further impressed to pull aside the curtain in

the rear of the plane. There, to my surprise, I found the

floor exit wide open.

I jumped. My feet struck mushy ice and I broke through

to the river bottom three or four feet below. Fortunately

I had no broken bones and was soon making my icy way, along with

others, to a sand bar four hundred yards distant. How we

found it and got there through the broken ice was a miracle.

When we did get there, it was only two or three inches above the

river.

It was low tide. This was very fortunate. But

soon the high tide would be running, and in this area it

sometimes reached a height of nineteen feet.

I was one of the two medics aboard. Neither of us had

any supplies on us and nothing was saved from the plane.

But we did what we could. The men who had fought their way

up and out through the top exit discovered they had to jump down

fifteen feet to the wing and then get off. Many were

injured. Some were knocked unconscious as they struck the

wing and fell into the water, where they drowned unnoticed in

the darkness.

The night was bitterly cold, about 10 degrees below freezing.

The right wing burned fiercely, but its heat warmed no one

except the dead. The fire did help, however, in guiding in

the air ambulances, which had been called just before the crash.

While waiting we checked the survivors, gave what first aid

we could, and decided on the evacuation order. Some of

those huddled on the rapidly disappearing sandbar were safe and

sound. Others were suffering from shock. Some were

badly burned from the fire, and others had broken bones.

After fifty minutes the first helicopter arrived, cautiously

feeling its way down with lights blazing. It stopped in

midair, hovering a few feet over the huddled crowd. On it

we sent out four or five litter cases. After it flew away

to the 121st Evacuation Hospital at Ascom City, all was dark

again.

There was not even a flashlight in the group. Only the

plane blazing out in the river enabled us to discern the shadowy

frozen figures who had set out on a happy R and R tour to Japan.

It was cold. Our clothes, even our shoes, froze on us.

Soon all helicopters in the area were ordered to the scene, and

these aerial ambulances did a heroic rescue job. The high

tide was now rolling in from the sea and the sand bar was

rapidly falling beneath our feet, leaving us all standing

knee-deep or more in ice water.

It became apparent we could not all be flown out in time, and

it was decided, after first taking the most seriously injured to

the hospital, that the helicopters should just ferry us over to

the riverbank three or four hundred yards away. It was a

strange scene--a flock of spinning windmills picking us up one

by one or five by five or nine by nine, according to the sizes

of the various machines, and depositing us on the shore.

One man, in his excitement to get away from the engulfing

tide, hung onto a wheel as the helicopter took off. We saw

him hanging there and wondered. His benumbed hands soon

gave up the struggle and he fell into the river, but we

were able to rescue him. The last man ferried out had been

standing in water up to his neck.

It was then 11:00 p.m. and bitterly cold, but most of the men

were calm. Soon Korean farmers came from all directions.

They built fires, cut off frozen shoes, and rubbed icy feet back

to life. One Korean farmer used up all his winter fuel

supply of wood and straw trying to keep us warm. Korean

police and ROK Army ambulances also arrived and stood by.

One by one we carried the non-ambulatory victims on

stretchers to the ambulances or tied them to helicopters for

their aerial ride to Army hospitals. The other medic had

been evacuated by then, so I was the only one left.

At 1:45 a.m. we were still working, sending off the remaining

few, most of whom were able to walk. The wind had now

risen and the weather was frigid.

At 1:55 all the survivors had been sent on. My midnight

medic assignment over, I stood alone by the river.

All was quiet now. The muffled noises were silent.

Away out on the half-frozen river lay the dying embers of our

aerial chariot, its last flight over. One hundred and

thirty-four of us, including Captain Cartwright, were still

alive. But the other twenty-two lay silent around the

funeral pyre, or were strewn where they fell along the cold

countryside, or were being washed down the river under the ice.

I was thankful that so many were safely off to warm

hospitals. Never before had so many survived a Globemaster

crash. I was thankful, too, for the spectacular answer to

my own brief prayer and happy to have been of some help as a

lone medic at midnight on the frozen Han River. As I stood

there looking out over a scene strewn with broken and jagged

six- and seven-foot ice chunks, I realized that it was only by a

miracle that so many of my R and R companions and I had been

saved. A premature explosion of that plane, and death

would have claimed all of us.

At last General Gants, who had been surveying the wreck with

six or eight air and medical officers, approached and asked me

if all the living had been evacuated. Assured that nothing

more could be done, he invited me to leave with them.

As the helicopter rose into the air, silence again settled

down upon the river and nothing remained of the tragic scene but

the forty-eight-foot tail of the $1,700,000 plane.

We stopped and alighted a short distance away, where the

ambulances were still parked and waiting. At the

insistence of the ambulance corpsmen I was carried from the

helicopter to the ambulance fifty yards away, even though I had

spent much of the night carrying stretchers myself! They

said they didn't want to take any chances with me, the last

survivor.

It was two days before I could get through on the

trans-Pacific telephone to my wife and parents in Stockton,

California, who all the time had known I was on that very plane.

I went on to Japan on the next Globemaster, to continue my R

and R. We got there safely, but on the return journey,

just eight minutes after we left Tachikawa on the sister ship of

the one that crashed, the same inner starboard engine also blew

up. As before, it quickly caught fire, and we thought we

were in for another crash, and this time with no soft river to

land in.

Another Han River crash victim was aboard. He went

berserk, and the crew had to strap him to his seat. But

the propeller did not spin off and the fire extinguishers

quickly put out the fire.

Our pilot made a quick turn and was soon heading downward

toward those precious Tachikawa runways. There was no time

for the usual slow approach, and we landed at a terrific speed.

As we whizzed along that concrete strip we saw an escort of fire

equipment and ambulances racing along beside us.

We reached the end of the runway far too soon, and as the

plane made the inevitable turn, the landing gear on one side

gave way and the plane went over on the side. There was no

fire, and we soon unbuckled our safety belts and walked out of

the tipped-over plane to safety.

I am still in Japan. The authorities have given me the

privilege of returning by ship."

Roland's Letter

[KWE Note: The following eye-witness account of the C-124

Globemaster crash in the Han River was submitted to the KWE by

Forest Clough. The author of the letter was a survivor of the

crash whose first name was Roland. His last name has not yet

been identified, but it is believed by Forest that Roland was a

member of the Bell Family. Roland wrote the letter to his mom

and dad on March 20, 1957.]

Dear Mom and Dad,

I sure am glad to get the letters. They are better than

medicine 'coz they build the morale as well as the body.

Glad you are ok too, Dad. I got the cartweel [sic] and

have it in my pocket. Thanks a lot.

Seems as though Jim has exaggerated a little, Mom. You

said in a letter that you were sorry to hear that I lost a

finger. Well, I still have ten. I just had

the 3rd finger of my right hand cut. I cut it to the bone

and also the nerve. I have no feeling from the big knuckle

forward. Looks normal and I can still use it. All of

the injuries I received are as follows: I burned the back of my

left hand from gas on the water (burning gas), and cut my right

hand. If you draw a straight line from the tip of the

first finger to a point one inch behind the union of the little

finger to the hand, you can see how the cut on my right hand

was. Only the longest finger (3rd finger) was cut real

deep. I burned the tips of all fingers (both hands) and

the palm of my left hand and got the cut at the same time.

I attempted to lift a portion of the fuselage up to free a

lieutenant that was pinned from the stomach down so he could

leave the burning wreck. I was still in the plane then and

she was mighty hot. I am sorry to say that I failed to

free the man and as far as I know he either burned or drowned or

both. About one minute after I left the plane, the tanks

in both wings blew. There were 2340 gallons of aviation

fuel in them. Big Bang! Here's the story:

We boarded the C-124 at approx. 7:45 PM Thur, 22 Feb 57 at

K-14 (Kimpo), Korea. This was an R and R flight to Tokyo,

Japan. The pilot made all of the preliminary checks,

revving the engines, taxing, etc. Everything was normal.

Then we took off. The C-124 is a huge plane and is double

decked on the inside. There are 4 rows of seats on each

deck running parallel to the sides. 2 rows, back to back,

in the center and one row on each side.

I was sitting on the top deck, right side, center aisle, 3rd

seat back. Sgt. Meyers was on my left and Pfc. Junkrowski

on my right. We weren't up over 2 minutes when the plane

was jarred as if we clipped the top of some large trees.

Then there was a very cold draft. We started losing

altitude fast. (I guess.) I knew we were too high to

hit trees and when you dip suddenly your stomach jumps up into

your mouth. Mine jumped up and stayed in my mouth. I

tightened my seat belt and relaxed as much as I could.

Seemed like we were going to make it when the warning bell rang.

The pilot told us before we took off that 6 short rings meant

ditching. The bell rang 3 times and then we hit before he

could ring the other 3 times. Upon impact it seemed to me

that I was thrown forward and way under water. I didn't

think I was going to make the surface. When I did I was on

my hands and knees in the fuselage in about 2 feet of water.

Somebody came running past me completely on fire. There

was fire to the front of the plane, to the rear, and the

fuselage was collapsed on the left side and there was fire

there. Fire on 3 sides and fuselage on the right with fire

on the other side of it. There was enough fire to heat the

water. It was warm. I got my face and ears scorched

a little. I knew I was having trouble breathing but I

didn't know why then. I had my doubts about getting out,

too. Then I heard the Lt. call for help. I tried to

help him but couldn't. About then the fire to the front

died down momentarily and I could see it was only about 2 feet

thick, so I went through it and out into the Han River. I

couldn't swim because of my clothes and boots and the cold

water. So I attempted to float with the current. I

drifted about 20 yards when I came to an ice floe about 6 feet

in diameter. I climbed on it and stood facing the fire and

expected to wake up any minute. I thought it was a dream.

After awhile I managed to swim, wade and drift to the main

sandbar where the rest of the survivors were. By then my

ribs hurt so bad I couldn't stand up straight. About 1

hour later, during which time my clothes froze, I was taken to a

hospital in a helicopter. It was one of these jobs where

they tie you in a rack on the outside. I was colder than

cold. I wound up with 2 burnt hands and one cut as

previously mentioned, 2 broken ribs, one pulled tendon of the

right ankle and misc. small cuts and bruises.

A couple of days later investigation teams came around asking

questions to get an idea what happened. I then learned

what happened. We were in flight about 4 minutes.

Our estimated speed when we hit was 125 mph and from first

contact with the sandbar until we stopped was only 75 yards.

How about that? Imagine the momentum of the people and

loose things in the plane. That was a sandbar of solid

ice! Not one time did I see anything but plane, ice, and

water. The river was 1 mile wide here, they say.

The #3 engine is the inside engine on the right side and #4

is outboard right side. The propellers are 4 bladed, 16

feet in diameter, and turning 2400 rpm. The cause of the

crash was because the propeller came off of the #3 engine and

cut through the fuselage. It cut from a point about 8 feet

up from the lower floor to the floor and all the way across the

bill or floor. This cut the controls to the number 4

engine and also the controls to the ailerons and the tail assy.

All the controls to the #1 and #2 engines and the rudder.

When the controls to an engine are cut, it immediately goes to

idle. That pilot sat that C-124 down with only the 2

engines on the left side and the rudders. 137 of the 159

onboard survived. That's damn good! Only 22 dead.

The worst of it all is the fact that both Junkrowski and Myers

died, 2 of my best buddies. That prop when it came through

the plane must have gone under where I was sitting. When

the plane finally came to a halt, the nose had broken off when

the prop came through and folded back under the belly. The

tail section was on the sandbar and the nose was in the main

channel of the river. God was taking care of me this time.

I wasn't seriously hurt, but I was scared. I haven't ever

been quite so cold, either. So no sweat and don't worry.

It's all over now. Just between you and I -- I wish I'd of

had a parachute. Next time I fly, I will have one on or I

won't fly! Gotta write Jackie now, so be good and have

fun.

- Love, Roland

Back to Page Contents

Letter of Commendation from Major General Waldon

[KWE Note: The following letter of commendation was printed on pages 2 and 40 of the United States Army

Aviation Digest, Volume 3, May 1957 (Number 5).]

Headquarters - United States Army Forces Far East

& Eight U.S. Army (Rear)

Office of the Commanding General

APO 343, San Francisco, California

5 Apr 1957

Dear General Hutton:

Enclosed for your information is a copy of a letter from Major General R.L. Waldon,

Commander, 315th Air Division, United States Air Force, as endorsed by General Laurence S. Kuter, Commander,

Far East Air Force.... We in this command feel justly proud of the conduct of our officers and men in

meeting a hazardous and tragic emergency with valor and expediency. - Sincerely, I.D. White, General, United

States Army Commanding.

Headquarters

315th Air Division (Combat Cargo)

United States Air Force Office of the Commander

APO 323, San Francisco, California

7 Mar 1957

Subject: Exceptional Service

Thru: Commander, Far East Air Forces (Advance), APO 925

To: Commanding General, United States Army Forces, Far East and 8th United States Army (Forward) APO 301

1. On 22 February 1957 a C-124 aircraft of this command was forced to land in the Han

River near Seoul, Korea. There were 10 crew members and 149 passengers aboard.... There were 137

survivors.

2. Certain members of your command gave exceptional service in the rescue of survivors.

I refer to the pilots and other crew members of Army helicopters who evacuated the survivors to nearby

hospitals...a few minutes after the aircraft accident occurred 26 Army H-13 and H-19 helicopters arrived

at the scene of the accident. These helicopters, with the assistance of one Air Force helicopter,

evacuated all survivors.

3. This evacuation was accomplished during the hours of darkness. The helicopters

involved flew a total of 81 1/2 hours.... Since there were 27 helicopters participating in the rescue

operation, the resultant air traffic saturation created an extremely hazardous condition. The

selfless and heroic actions of your helicopter pilots and other crew members in evacuating the

survivors to nearby hospitals unquestionably prevented the death toll from being higher. If

evacuation from the sand bar had not been affected, the rising tide and freezing water might have

resulted in there being no survivors. I recommend that these men be given special recognition and

high honor.

4. According to available information, the Army helicopters and crews involved were

assigned to the following units:

-

Korea Military Advisory Group

-

K-16 Helicopter Ambulance Detachment

-

A-9 unit of 24th Infantry Division

-

3rd Light Aviation Section of 1st Corps

-

2nd Engineer Group Air Section

-

13th Transportation Company

5. There were many individuals who gave aid and assistance on the night of the accident

and during the recovery and salvage operations which extended over several days. Many of these

persons should be singled out for special praise. However, we have no information as to the names

of most of these people. I regret that each of them cannot receive the honor and recognition due

him.

6. ... Personnel of the 121st Army Hospital did their utmost to relieve the suffering of

the accident survivors, many of whom had sustained cuts and burns...we also desire to express our

special thanks to all your personnel who assisted in the recovery of No. 3 engine from the accident

site. This was almost a superhuman task because of the icy water and tide conditions. Only

by examination of this engine will the cause of the accident be determined.

7. There are 7 individuals I would like to commend for their prompt and valuable aid in

the recovery efforts following the accident. They are:

-

Colonel John W. Maxwell, The Quartermaster, AFFE/8th Army

-

Colonel K.W. Dalton, United States Army Operating Group

-

Colonel Thatter P. Leber, 2nd Engineer Construction Group

-

Major Kilcauley, Transportation Corps, United States Army Port, Inchon

-

Captain John P. Denham, 5th Quartermaster Detachment, Petroleum Laboratory

-

Captain William J. Roof, 540th Quartermaster Company

-

CWO Mielnik, Harbor Master, Inchon Post

8. It is requested that a copy of this favorable communication be filed in appropriate

records of each individual concerned.

(signed) R.L. Waldron,

Major General, United States Air Force Commander

Headquarters, Far East Air Forces, 9 Mar 57

To: Commanding General, United States Army Forces, Far East and 8th United States Army (Forward), APO

301:

1. The foregoing letter by General Waldron has my wholehearted endorsement. It is a most deserving

tribute to the Army personnel, each of whom so willingly and courageously risked his life to assist in the

rescue of his fellow serviceman.

2. The indomitable courage demonstrated by the personnel who took part in this operation is surely a

credit to the United States Army. Their efforts will undoubtedly be a source of pride to the

organizations represented.

(signed) Laurence S. Kuter,

General, United States Air Force Commander

Back to Page Contents

Rescue/Recovery Efforts

Han Search Continues But Hope Dims for 17

[News clipping submitted to the KWE by crash survivor Arnold Silveri]

"SEOUL (S&S Korea Bureau) - Seventeen American servicemen were still missing Monday morning after a

huge double-decked C-124 transport burned after a crash landing Friday night on a Han river sand bar. Of

the 22 passengers originally listed as missing, bodies of five have already been found. The remainder of

the 159 passengers and crewmen survived. Twenty-eight are hospitalized, two in serious condition.

Bodies of a number of the missing are believed pinned under the top deck of the Globemaster which

collapsed onto the lower deck in the crash. High tides from the Yellow Sea and big chunks of floating ice

are hampering salvage operations. Low-flying aircraft and ground crews continued to search the ice-caked

banks of the Han Monday morning with no success reported as late as 10 a.m."

13 Still Missing From C-124 As Workers find 9th Body

[News clipping submitted to the KWE by crash survivor Arnold Silveri]

"SEOUL (S&S Korea Bureau), February 26, 1957, p. 11 - An Air Force spokesman reported Monday that four

more bodies have been recovered from the wreckage of a C-124 Globemaster which crashed Friday on a Han

River sand bar. Recovery of the bodies brought the death toll to nine with 13 still unaccounted for.

Maj. Raymond A. Day, operations officer at Ashiya AB, said three of the bodies were those of passengers

and the fourth that of an Air Force crewman. Recovery of the bodies Monday was made by Air Force

helicopter rescue teams. Mud, ice and rushing tides hampered raising of the gutted plane's forward section

from the water.

A pocket of quicksand in shallow water near the crash also prevented the use of an Army bulldozer and

crane-equipped tank retriever in the salvage operation.

Of the 137 survivors of the crash, 28 are still hospitalized. Two severely-burned victims Monday were

removed from the "critical" list at the 121st Evac. Hospital at Ascom City. Spokesmen said an all-out

effort was to be resumed Tuesday to lift the wreckage from the sand bar.

Teams Recover 10th Globemaster Crash Victim

[News clipping submitted to the KWE by crash survivor Arnold Silveri]

"SEOUL (S&S Korea Bureau) - Army engineers, graves registration workers and Air Force "para-rescue"

teams continued their fifth day of grim work in the Han River Wednesday and recovered the body of a 10th

victim killed in Friday night's crash of a C-124 Globemaster. The workers then spent four hours in water

around the narrow sand bar on which the huge plane crash-landed and burned, trying to recover another body

pinned in the wreckage. High tides rolled in at 4 p.m., forcing salvage crews to give up again. The

salvage operations and efforts to recover the 11th body were scheduled to resume at 10 a.m. Thursday, an

Eighth Army spokesman said.

Demolition charges exploded at intervals by the 44th Eng. Const. Bn. Tuesday night prevented the

plane's wreckage from being too-heavily covered under ice. At approximately noon Wednesday, a heavy charge

cleared the way for rescuers to probe for two bodies spotted beneath the ice late Tuesday. A bulldozer on

the rim of a levee 200 yards away pulled down the blast-loosened wreckage with a winch and nylon rope.

The first body was pulled up at 2 p.m., an Eighth Army spokesman said. Graves

Registration workers of

the Eighth QM Gp., wearing heavy "survival suits," then waded chest-deep into the freezing waters in an

attempt to recover the second body. "It was slow, reverent work to them," a spokesman said. "They refused

to use hooks and ropes. and they were in the water for a long time." He said the workers had nearly the

body from the ice-trapped wreckage when the tide, which had reached a height of 19 feet, forced the

salvage group to withdraw to the levee via helicopter.

While they could, the spokesman said, the workers made the most of time and material. They didn't even